UK booksellers Mark James and Anke Timmermann of Type & Forme have launched a virtual exhibition and accompanying catalogue to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Captain Cook’s arrival in Australia. Botanist Joseph Banks was along for that ride aboard the Endeavour, and during the voyage from Brazil via Tahiti and New Zealand to what would later become Queensland, Australia, he discovered and documented 1,300 previously unknown botanical species.

It was Banks’ plan to publish a full catalogue of the drawings by the ship’s artist Sydney Parkinson, and to that end, upon his return to London, he employed a team of engravers to produce copper plates of the drawings, but it was an enormous and costly job. At his death fifty years later in 1820, the Florilegium remained unfinished. Two small editions were published in the twentieth century, culminating with a color edition of the surviving 738 plates printed between 1980 and 1990 by Alecto Historical Editions in association with the British Museum. The ten plates spotlighted for sale in the accompanying catalogue are from that printing, limited to 116 impressions.

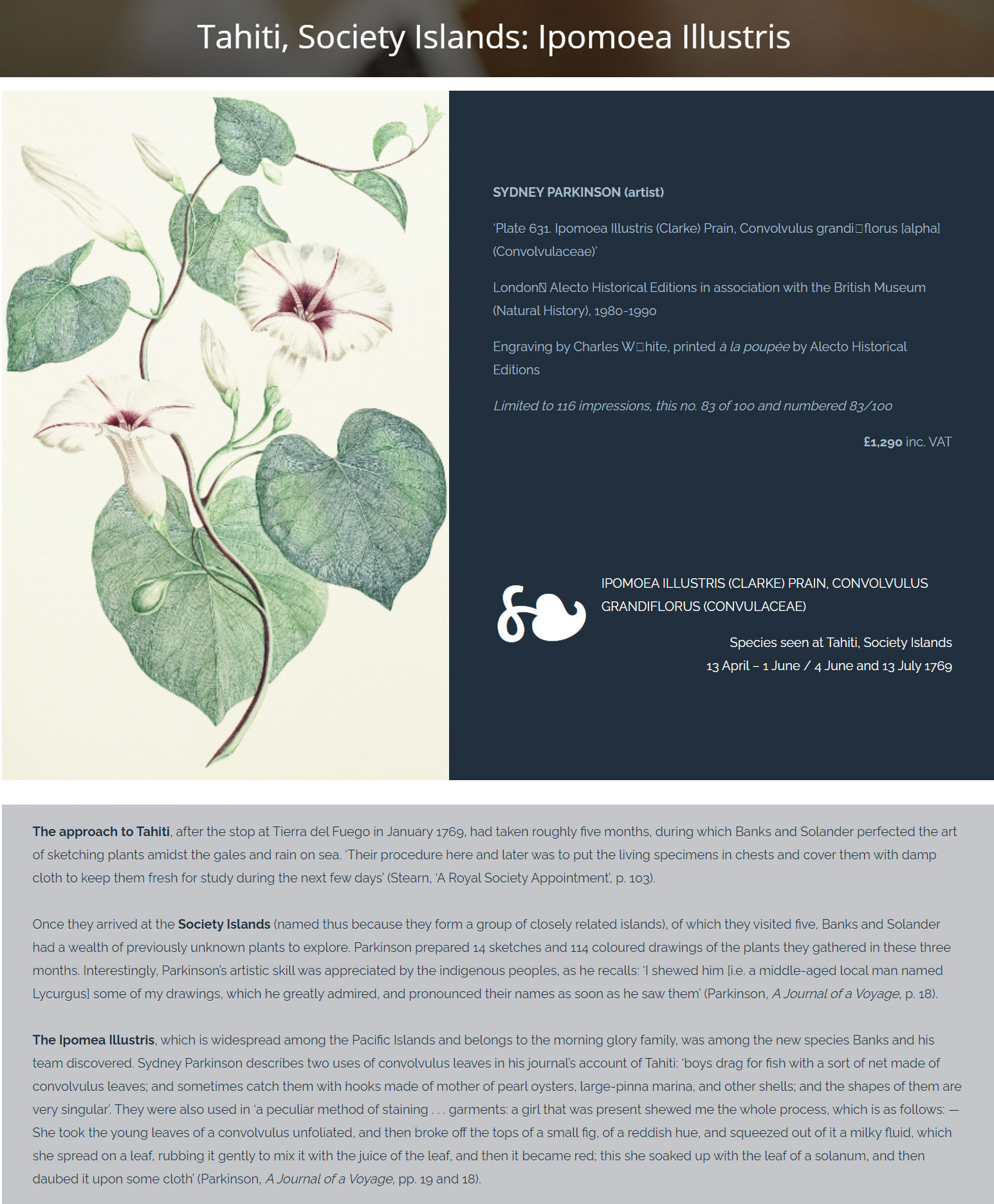

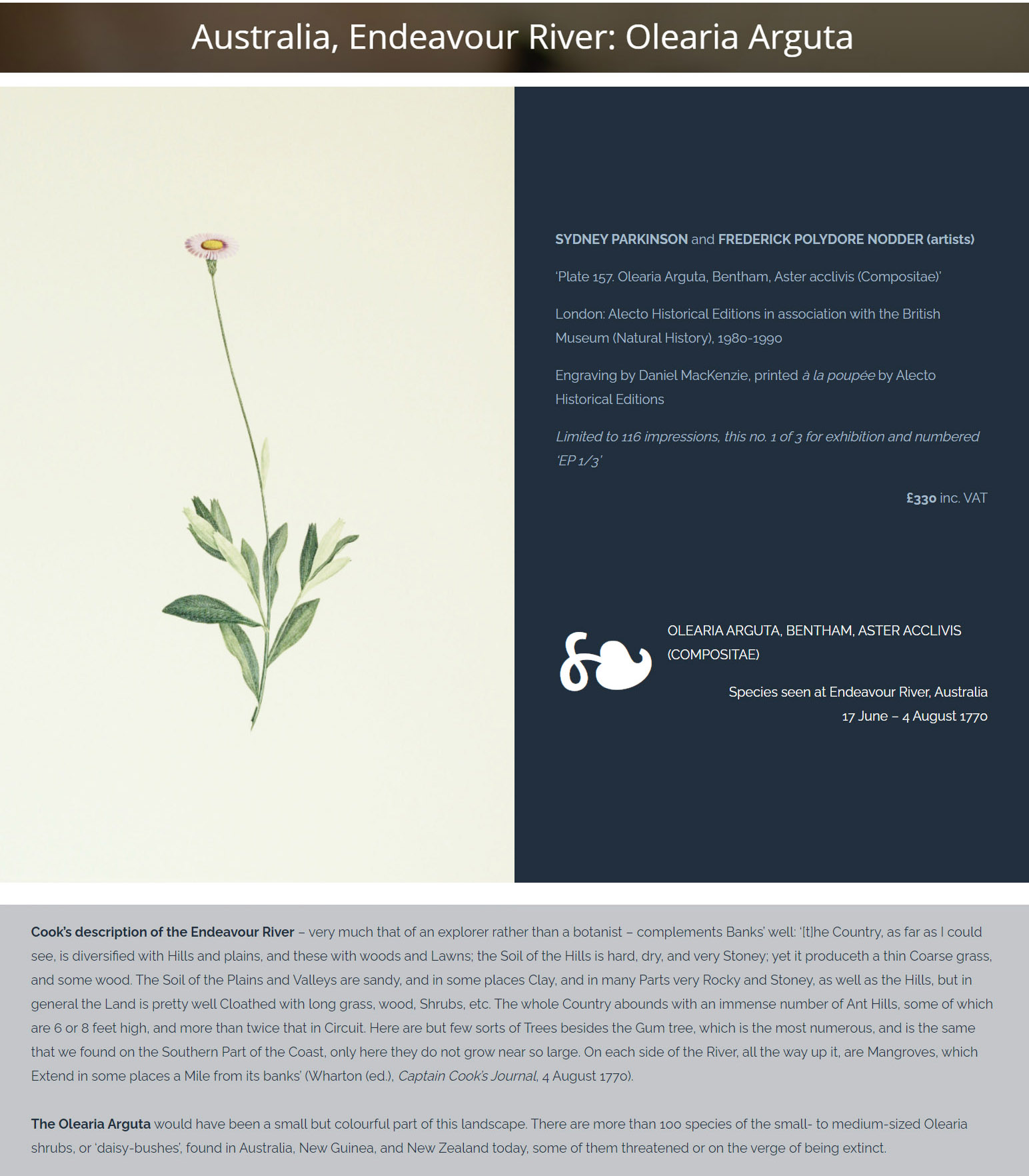

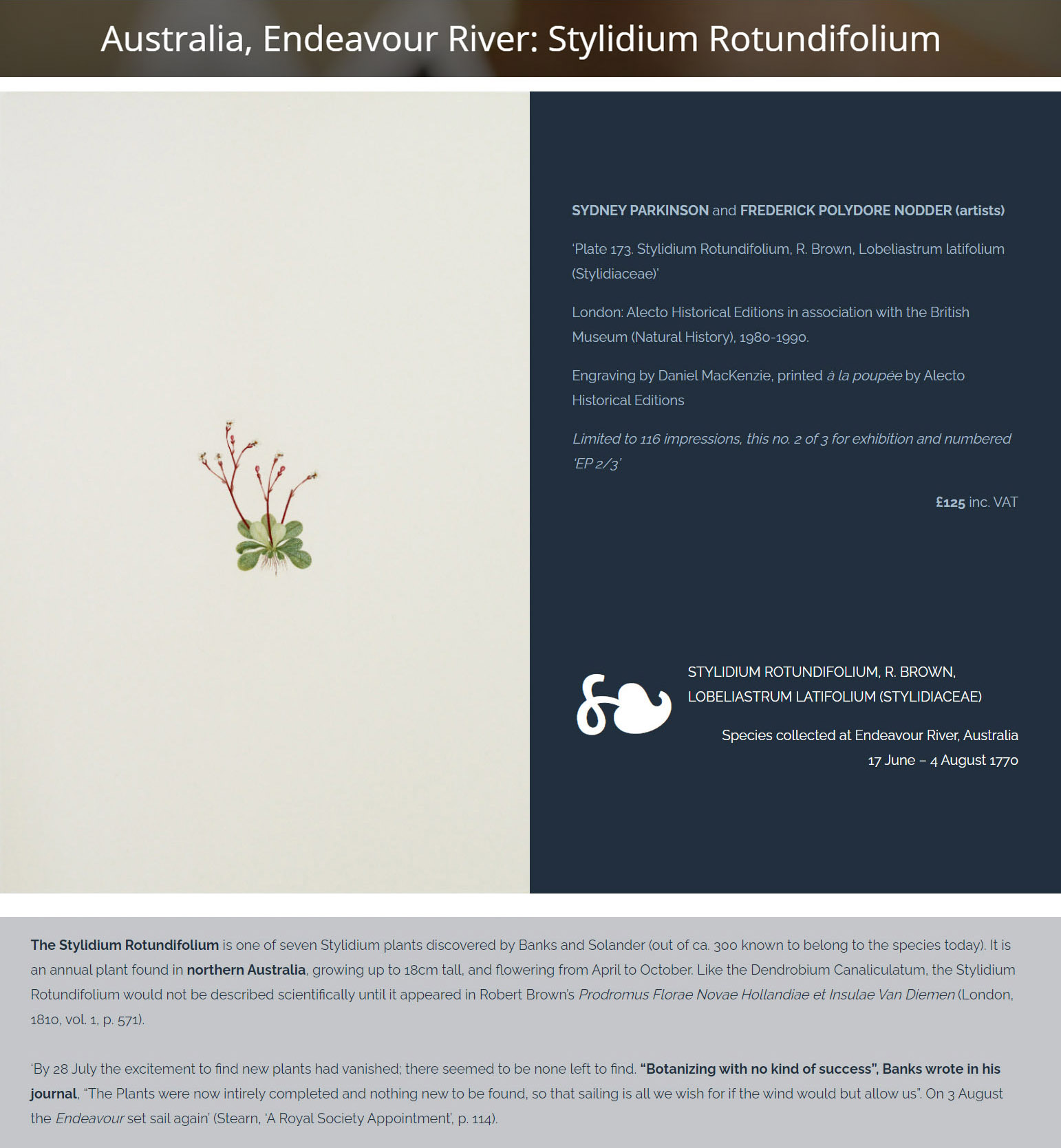

Type & Forme’s online exhibition, Joseph Banks: A Lincolnshire Botanist in Australia, which runs throughout June 2020, showcases the production of the Florilegium engravings, a collaboration of botanists, artists, engravers, and printers over 200 years. By clicking through the various plants and flowers, you can follow along in Banks’ footsteps, plucking the Temnadenia Violacea in South America and the Stylidium Rotundifolium in northern Australia.

Exhibition – Joseph Banks: A Lincolnshire Botanist in Australia

250 years ago Captain James Cook and his crew – among them the Lincolnshire botanist Joseph Banks – became the first Europeans to set foot on the eastern coast of Australia.

His Majesty’s Bark Endeavour had been sent to the Pacific with the purpose of observing the 1769 transit of Venus across the sun, launching from Plymouth in 1768, and approaching New Zealand via Brazil and the Society Islands in the course of the following nine months.

But it was Cook’s decision to proceed via the east coast of the continent then known as New Holland in 1770 that would be the first step towards the British settlement of Australia – a fundamental moment in the history of exploration and science.

Joseph Banks’ botanical discoveries – some 1,300 previously unknown botanical species – revolutionized European understanding of natural history.

The ten prints presented in this exhibition show the rich foliage, colourful flowers, and diverse species that Banks discovered as the Endeavour traversed the globe.

Some of the plants would, in time, travel to Europe, and thus form part of our flora today; others have become extinct, meaning that Banks’ specimens and drawings documenting them are especially important; and yet others will be familiar to those who have travelled to the shores on which the Endeavour first visited two-and-a-half centuries ago. Together they form a botanical history of parts of the world that had only been seen by very few, if any, western travellers before.

Joseph Banks: The History of his Florilegium

SIR JOSEPH BANKS BT (1743-1820) first dedicated himself to the study of the sciences, especially botany, while a student at Christ Church, Oxford. Upon inheriting Revesby Abbey, Lincolnshire in 1761, he focused his research on collections of the Chelsea Physic Garden and the British Museum, where he met Daniel Solander, one of Linnaeus’ students.

In 1766 the young Banks ‘served his apprenticeship as a scientifically trained Linnaean naturalist – as opposed to an undiscriminating virtuoso gentleman collector – by accompanying his old Etonian friend, the naval officer and future MP and lord of the Admiralty, Constantine Phipps, on an expedition . . . to Labrador and Newfoundland. Though Banks was the sole naturalist on board, Solander assisted him in his choice of equipment and reference works’ (ODNB).

This ‘apprenticeship’ with Phipps ‘served as a virtual rehearsal for the great Endeavour voyage of 1768 to 1771’ through which Banks became ‘a figure of international scientific significance . . . The Endeavour expedition made it possible for Banks to explore a whole portion of the globe hitherto largely unexposed to European gaze’ (loc. cit.).

THE SEEDS FOR BANKS’ FLORILEGIUM had been planted with his earliest expedition: on his return to London from Labrador and Newfoundland, Banks had commissioned the young Scottish natural history artist Sydney Parkinson to draw some of the natural history specimens from the expedition on HMS Niger. On the Endeavour, Banks took both Solander and Parkinson (who sadly died at sea in January 1771) with him as members of his scientific party. On his return to England Banks planned an account of the expedition’s botanical discoveries, and employed a team of engravers to produce copper plates of Parkinson’s drawings. 743 plates were engraved under Banks’ supervision by eighteen engravers over a period of thirteen years, at a cost of more than £7,000. Manuscript descriptions of the specimens were prepared by Daniel Solander, but (apart from some small groups of proof plates) the long-anticipated work remained unpublished at Banks’ death in 1820, nearly fifty years after he had returned from the Endeavour expedition.

ON BANKS’ DEATH, the engraved copper plates were bequeathed to the British Museum, where they remained in storage until 1900-1905, when monochrome lithographic plates of the Australian flora were made after the original plates (British Museum, Illustrations of Australian Plants, reproducing 320 of the 743 images). The 1973 limited edition (100 copies) of Captain Cook’s Florilegium, edited by Wilfrid Blunt and W.T. Stearn included a small number of engravings printed from the original copper plates in black ink only.

IT WAS NOT UNTIL 1979, following successful trial printings of the plates in colour, that Alecto Historical Editions and The British Museum (Natural History) agreed to jointly publish the full set of 738 plates (five of the original 743 had been stolen), printed in colour à la poupée (i.e. by applying the colour to the plate with a cotton ball, and then adding further colour if necessary with a brush). Only 100 sets of Banks’ Florilegium, which appeared between 1980 and 1990, were printed for sale (of which all were subscribed), together with sixteen further sets, comprising three printers’ proof sets (of which number 1 is at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew); three sets printed for exhibition purposes; and ten hors commerce sets (120 plates from set no. VII were sold by Sotheby’s, London in 1988 to benefit the Banks Alecto Endeavour Fellowship, and sets IX and X went to The British Museum, Natural History).

THE RECEPTION WAS ENTHUSIASTIC: The Book Collector (vol. XXXVIII, 1989) considered the Alecto edition ‘a triumph on many scores: a triumph of imagination, to conceive such an enterprise; a triumph of aesthetic sensibility, to realize that plates originally intended to be printed in black could be rendered in colour with such magical beauty, yet true to nature; a triumph of technical skill, to restore the tarnished plates and print them with unerring precision, maintaining the same high standard from first to last . . .; a triumph, above all of tenacity to bring such a colossal enterprise . . . to a final successful conclusion’.

Joseph Banks: Gallery

View the story and gallery on the Type & Forme website.

Download the catalogue for Joseph Banks: A Lincolnshire Botanist in Australia.