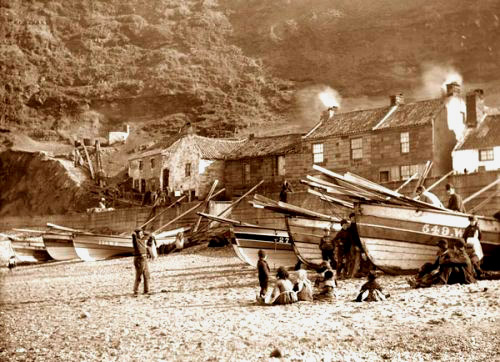

Staithes looking towards the sea, 19th century

Staithes (1745-1746)

James Cook at Staithes

By Anne Dennier. Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society / Whitby Museum

When young James Cook left his father’s cottage on Airyholme Farm near Great Ayton in1745 to take up a new life at Staithes, he exchanged the wide open fields of the Tees Valley, with its green fields spread out below the hills of the Cleveland escarpment, for a village of some 800 souls crowded together at the head of a little bay enclosed by cliffs some 50 metres high, looking out northwards to the sea. All his sixteen years or so he had lived on a farm and among people who gained their living almost exclusively from agriculture. Now he was to live in a community which relied entirely on the sea – and for the most part on fish – for a living and was to learn about shop-keeping in a local store belonging to Mr William Sanderson.

South East View of House Built by Cook’s Father in Great Ayton, by George Cuit

Staithes was already an important fishing village on the Yorkshire coast. It lies some 12 miles north of the port of Whitby. Staithes was not an easy place to reach by land so the sea was for many the better way to travel. Roads were poor; many routes no more than pannier tracks (stone flags laid end to end) across miles of heather moor, now celebrated as a National Park. The hazards of lonely heath, bogs, hills and steep-sided valleys were only too real in former times. Despite this Staithes people managed to send some of their catch fresh, by pony, to inland markets, including York, though most of it was preserved by drying or salting and marketed later, often taken as a cargo to an east coast port, London or possibly farther afield.

19th Century View of Staithes, by W. G. Tennick

Depending on the time of year the main catch varied from herring to cod or to crab and lobster with some salmon fishing. For the herring and the cod especially the men took their boats on long journeys. The herring shoals were followed down the east coast of Britain in late summer and autumn to the rich grounds off the Norfolk coast; at other times the men would venture far out to the Dogger Bank for cod, again spending many days away from home. The North Sea (then called the German Ocean) is not easy to navigate and is subject to ferocious and sudden storms. Northerly and easterly winds blowing directly onto the coast are particularly dangerous. Staithes, facing into the teeth of such storms, suffered badly and from time to time parts of the town were destroyed by the sea. The area of flat land by the sea is smaller today than it was in Cook’s time. Indeed Mr Sanderson’s shop was destroyed in just such a storm in 1767.

Hauling Herring Nets

The fishermen used smaller boats for inshore fishing called cobles, and ‘five man boats’ (yawls) for fishing in more distant waters. Cobles are found elsewhere in the British Isles adapted to the particular conditions of their area. The Yorkshire coble , usually manned by three men, varied in size but could be more than 20 feet (6 m.) long. They were designed to cope with steep shores and lively seas so had a sharp bow but no keel to speak of; instead there was a substantial rudder which could easily be unshipped before landing since cobles must be taken ashore stern first. They could be lifted onto a larger boat or onto dry land, essential for their safety when a storm threatened. Some cobles were built in Staithes but the larger yawls were more likely to be built in Whitby. These had three masts and in Cook’s time probably had square sails. They belonged to local people who held shares in them. In Staithes most were owned and manned by members of the same, wide, family. James Cook would very soon have become familiar with the boats themselves, with the boys of his own age who worked on them and with all the concerns of weather, fish stocks and trade which dominated life in the village.

Cobles on the beach at Staithes, by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe

Though little is known of James Cook’s life as a shop-keeper’s assistant in Staithes it is easy to conjecture that his job may have seemed rather dull and confined by comparison with the men and boys he saw going off on journeys to places he had only heard of and coming back with interesting tales. He would also have seen larger vessels passing Staithes on their way to distant ports. We may guess he found the sea and boats attractive and showed some aptitude for sailing. We know very little about Mr Sanderson other than that he was a prominent and busy member of the local society. He evidently travelled about and attended the assizes, a well-recognised opportunity for meeting the great and the good in any County in England at the time, and no doubt had many business interests in the wider area. In any event, after rather less than two years it seems that he arranged for young James to move to Whitby to learn to be a seaman under the care of Capt John Walker.

South East View of Whitby, by George Cuit

Whitby Shipping in the 1740s

Ship building at Whitby began in the seventeenth century, it is thought in response to the demand for fuel for processing alum shale found in nearby coastal cliffs. The coal mines of Durham and Northumberland were the nearest source and ships were needed to bring it in as well as to export the finished alum. Once they were built they could carry coal to London where demand rose steadily, and profit in trading other bulky cargoes such as timber from the Baltic. The favoured design was therefore the Whitby Cat; a three-masted ship with a relatively shallow draft, usually between 200 and 500 tons burthen, built with a rounded hull so that it could carry a good weight and could take the ground easily allowing cargoes to be unloaded, on a sandy beach for example, when there was no wharf available.

Whitby “Cat” in Whitby Harbour, by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe

By the time James Cook arrived in Whitby though ship building was very important to the local economy, several owners had also developed a considerable role in merchant shipping. Initially it was usual for people in the town to spread the risks by taking shares in several ships both as they were built and when they were trading. Contacts were established all round the coasts of the German Ocean but especially with London, the Baltic ports and some French ports. As trade developed so investment rose. By the mid-eighteenth century the insurance industry was beginning to thrive and with this method of spreading risk several families in the town began to concentrate their investments by trading in their own ships. The Walker family was one such. However shipping was as risky a business as any. Profits went down in times of depression as happened in the 1720s and 1730s but things improved again by the 1740s. War was often the trigger; the dangers of sea travel increased prices and the Navy found the carrying capacity of Whitby ships and their sound construction made them well worth hiring as transports. It has to be said, too, that the government relied on the merchant shipping industry to train the seamen they would need in times of war. The north east coast ports on the Tyne and Wear, Newcastle, Shields and Sunderland, as well as the smaller ports along the coast such as Whitby played a considerable part in this enterprise.

References

Staithes. Chapters from the history of a seafaring town. John Howard. Published for John Howard, 2000. ISBN 0-9539005-0-9

Yorkshire Fisherfolk. A social history of the Yorkshire inshore fishing community. Peter Frank. Phillimore & Co., Chichester. 2002. ISBN 1 86077 207 2

The Rise Of An Early Modern Shipping Industry. Whitby’s Golden Fleet, 1600 – 1750. Rosalin Barker. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, Suffolk. Regions and Regionalism in History Series. 2011. ISBN 978-1-84383-631-5.