Maori Man, New Zealand

In Search of a Southern Continent

By John Robson, Writer and President of Captain Cook Society

Lieutenant James Cook (he was not yet a Captain) began his first voyage to the Pacific Ocean on 26 August 1768 when his ship left Plymouth. It was the start of a three-year voyage that would totally change his life. Astronomers had calculated that a Transit of Venus would take place in June 1769. British scientists from the Royal Society argued that Britain should play its part and send people to different parts of the world to take observations. The Pacific Ocean was expected to be the best place to watch the Transit so the Society asked the Royal Navy for a ship to transport them there. They also nominated one of their members, Alexander Dalrymple, to command the voyage. Dalrymple believed that a very large mass of land, a Great Southern Continent or Terra australis incognita, would be found in the South Pacific region. The Admiralty, the governing body of the Royal Navy, agreed to supply a ship but would only allow one of its own officers to command it. A search was made and a collier, The Earl of Pembroke, was selected as the ship. The ship, which had been used to transport coal from the River Tyne to London, was cleaned up, modified and renamed H.M. Bark Endeavour.

HMS Endeavour by Samuel Atkins c.1794

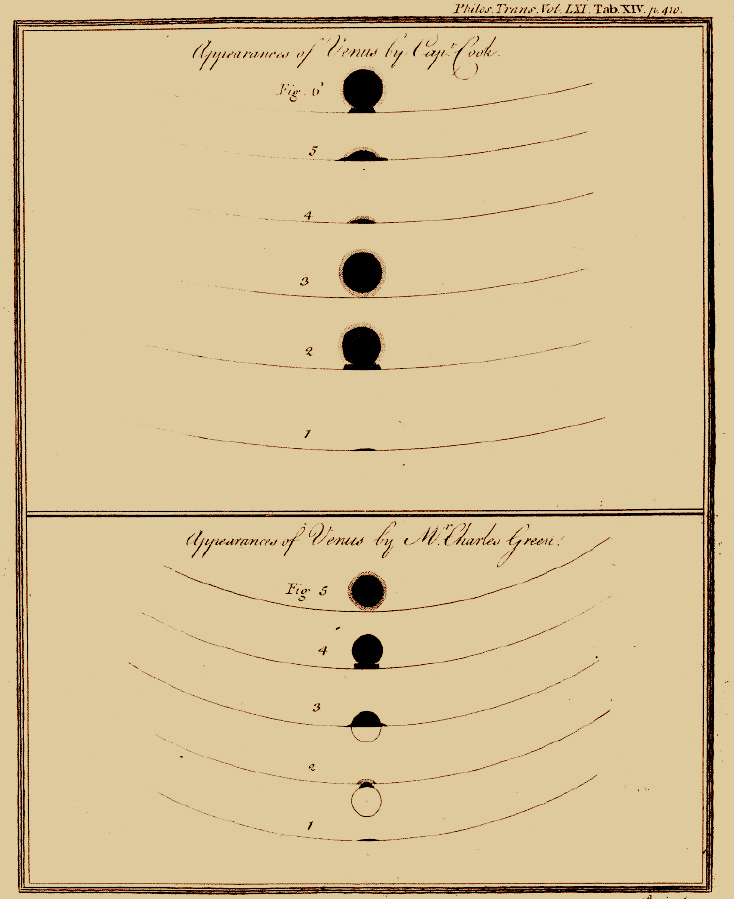

The Admiralty next looked for someone to take charge of the ship. Their choice was James Cook, not yet an officer, but a sailor of considerable experience. He had risen to the rank of master and had spent several years surveying the coastline of Newfoundland. He had also worked on the North Sea coal trade so was acquainted with ships like the Endeavour. In 1766, Cook had observed a solar eclipse while surveying the coast of southern Newfoundland and described the details in a paper for the Royal Society. His astronomical skills helped persuade the Royal Society of Cook’s suitability. He would assist Charles Green, who had been chosen by the Astronomer Royal to lead the observations.

In early 1768, Captain Samuel Wallis returned to Britain from the Pacific where he had visited the island of Tahiti. He reported positively about the island and its people and, as it lay in an ideal place, it was chosen as the location for observing the Transit. The British Government decided that the Transit’s observation would not be the only objective of the voyage. It prepared secret instructions for Cook for him to carry out after Tahiti in which he was to search the Pacific for the Great Southern Continent.

Sketches of the 1769 Transit of Venus, by James Cook and Charles Green

Joseph Banks was a rich, amateur scientist and member of the Royal Society, who wished to go on the Endeavour voyage and offered the Navy money to pay for himself and a party of scientists, artists and servants to travel. The offer was accepted and the ship was modified to accommodate them. Their presence helped make the voyage a memorable one as it became one of the first where science played an important role.

Dr Daniel Solander, Sir Joseph Banks, Captain James Cook, Dr John Hawkesworth and Earl Sandwich

by John Hamilton Mortimer, 1771

The Endeavour, only 30 metres long and with 94 men on board, sailed out into the Atlantic and made for the island of Madeira. Cook was determined to run a healthy ship. To this end, he made all the crew bathe themselves and wash their clothes regularly. He also made them clean and air the ship often. Most importantly, he insisted that their diet would be as healthy as possible in an attempt to offset scurvy, the scourge of long sea journeys. At Madeira, he took on board fresh meat, fruit and vegetables (he would try to do this at all ports of call), including a large load of onions for making sauerkraut.

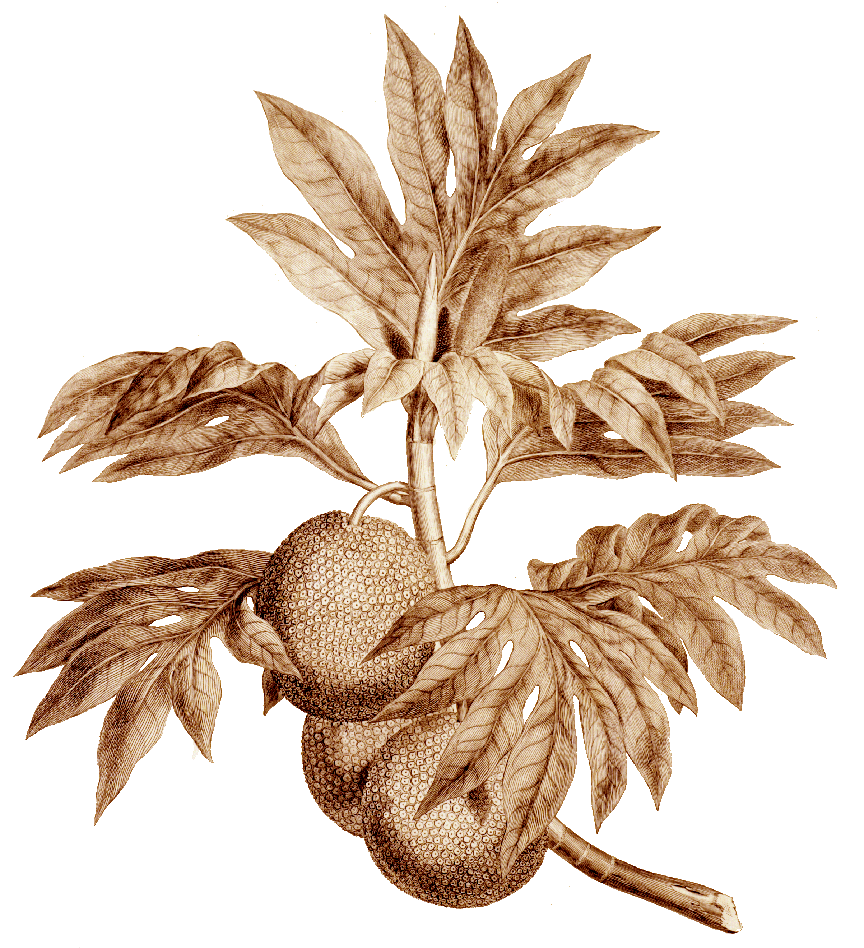

In Tahiti, Cook and Banks recognized the nutritional value of Breadfruit and later lobbied for it to be brought to the Caribbean to be grown on British plantations to feed slaves (Hawkesworth, vol. 2, plate 3)

The Endeavour continued down the Atlantic, calling in at Rio de Janeiro, before rounding Cape Horn to enter the Pacific. In April 1769, Cook reached Tahiti in plenty of time to prepare for the Transit. The British were allowed to build an observatory at Point Venus, close by their anchorage in Matavai Bay on Tahiti’s north coast. The astronomers successfully made their observation of Venus on 03 June. Cook then made a tour of the island with Banks and together they recorded the life and customs of the Tahitian people. When they left Tahiti on 13 July, Banks persuaded Cook to take Tupaia, a Raiatean, with them. This was a good move as Tupaia proved an able navigator and interpreter.

Tahitian Boats in Matavai Bay, Hawkesworth, vol. 2, plate 4 (click to enlarge)

The British called in at several neighbouring islands before Cook sailed the Endeavour southward. He had opened the second part of his instructions. Over the next two months they searched the ocean without finding the southern continent. Cook was already beginning to doubt its existence and decided to make for New Zealand, sighted 130 years earlier by the Dutch sailor, Tasman.

Tupaia’s Chart of the Islands Surrounding Tahiti c.1769 (click to enlarge)

On 08 October he reached land and Cook spent the next six months sailing around New Zealand proving it was not part of a continent. He produced wonderful charts of the islands. However, his encounters with Māori, the local Polynesian people, were not always the best and on some occasions Māori were killed, much to Cook’s regret. Tupaia was most useful as a translator, helping the two sides understand each other better. Cook and Banks wrote the first descriptions of the Māori, while Sidney Parkinson, the artist on board drew their likeness.

French Copy of Cook Map of New Zealand, 1784 (click to enlarge)

The Endeavour was ready to return to Britain and it was decided to go via Batavia (Jakarta) in Java where the ship could be repaired. Cook sailed west and on 19 April 1770 reached more land. This was New Holland, later to be called Australia. Sailing north up the coast, Cook found a bay, which he entered and where he stayed a week. He called it Botany Bay after Banks had collected many plant specimens. The local people, Aborigines, kept their distance and contact was minimal. Cook continued north up the coast and encountered the Great Barrier Reef. Disaster struck on 11 June when the Endeavour ran aground on the coral. It took a day to refloat the ship and it was nursed into the mouth of a nearby river (later called the Endeavour). The British were stuck there for two months while holes in the ship’s side were repaired.

Endeavour Beached for Repairs, Hawkesworth, vol. 3, plate 19 (click to enlarge)

Finally, in August, they sailed and passed through the Torres Strait between Australia and New Guinea. Cook was able to sail west and reached Batavia in October. The Dutch, who controlled Batavia, agreed to repair the ship but they were very slow and the British had to wait. While they waited many men became ill and eventually many died from diseases contracted in Java. Cook’s good work keeping a healthy crew free from scurvy was undone as men died on the crossing of the Indian Ocean to Cape Town.

Prospect of Town of Batavia and View of Citadel of Batavia, by Emanuel Bowen, 1774 (click to enlarge)

After a brief stop at the Cape, Cook sailed up the Atlantic. He had largely disproved the idea of the Southern Continent but was forming a plan for another voyage sailing further south closer to the pole. The reception in Britain was fantastic but it was mainly for Banks. Cook was still unknown to most people and he returned quietly to his wife and family in Mile End, London.

Antonio Zatta Map showing route (in red) of Cook’s First Pacific Voyage, 1776 (click to enlarge)

The Admiralty, however, recognised Cook’s considerable role in the success of the voyage. The logs, journals and charts, together with the scientific specimens collected and described, the descriptions of people and the drawings and paintings, were a wonderful record of an exceptional voyage. Cook had carried out his instructions and brought home the ship and a healthy crew (despite Java). The Transit of Venus had been observed and Cook had made a search for the Great Southern Continent. For Cook, though, it had only been a start. He had already formulated plans for another voyage to search for the continent and settle its existence once and for all.