View of Greenwich from Deptford / Harrison’s History of London c.1777 (National Maritime Museum)

Commander of Pacific Voyage (1768)

By Nigel Rigby, Writer and Curator at National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

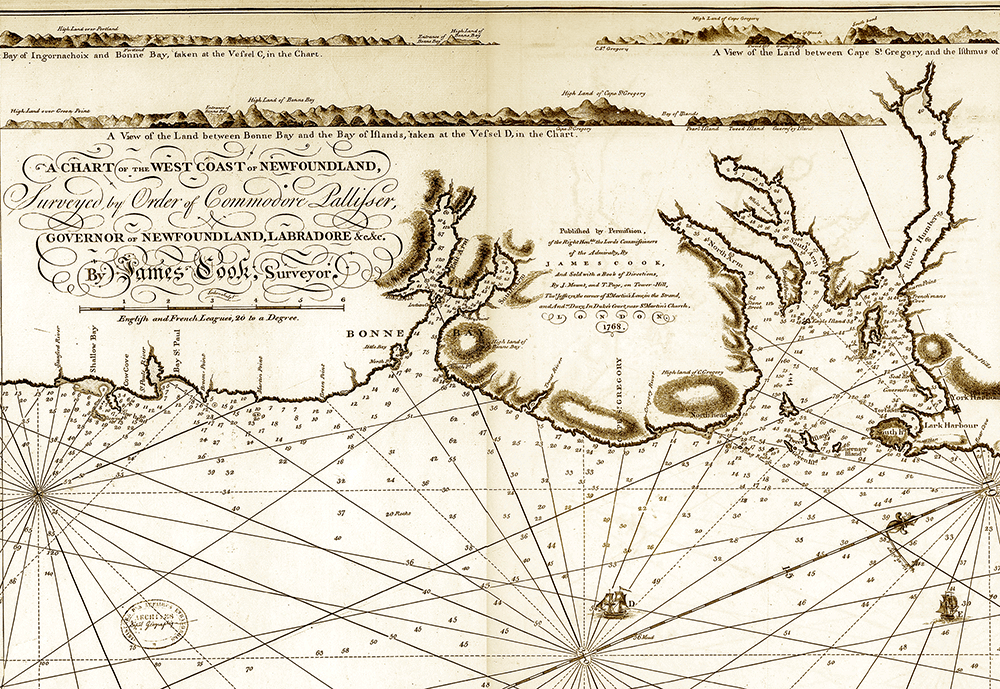

James Cook established a reputation as navigator and surveyor of exceptional competence in North America. He was a master – a non-commissioned officer – but one more than capable of working independently and using his own initiative. He had gained the attention, trust and respect of Alexander Lord Colville, his captain on the Northumberland, and Hugh Palliser, his captain on the Eagle, later governor of Newfoundland, and still later comptroller of the Royal Navy. Both men had supported his appointment to survey the complex coast of Newfoundland and Palliser’s patronage, in particular, would play its part in the next phase of Cook’s naval career. Cook had also come to the attention of Philip Stephens, the experienced, highly intelligent and quietly persuasive secretary to the Admiralty who had briefed Cook on the Newfoundland survey in 1763.

Hugh Palliser by George Dance the Younger (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Outside the Navy, Cook was becoming known in scientific circles, for his charts were beginning to be published. Following his observation of a solar eclipse in 1766, his findings were presented at the Royal Society of London, the influential body formed a hundred years earlier to promote and support scientific inquiry. As many have remarked, by the time of Grenville’s annual return to Britain in the winter of 1767/8, Cook’s skills and experience made him well qualified to command the voyage of scientific exploration to the Pacific that was being proposed by the Royal Society. Well qualified, though, is not the same as obvious, and Cook’s name appears not to have been coupled with the voyage until shortly before he was due return to Newfoundland in the spring of 1768. In fact, the appointment of a commander for the imminent Pacific voyage was a saga of poor communication, misunderstandings, self-promotion and dashed hopes.

Center panel of Cook’s Chart of the West Coast of Newfoundland, published in 1768

The sole original purpose of the Endeavour voyage, as it has become, was to observe the 1769 transit of Venus from a position in the South Pacific. Venus passes between the Sun and the Earth twice every hundred years or so. The transits come in cycles with the pairs eight years apart. Theoretically at least, if a transit could be observed from different locations around the world, it would be possible to calculate the distance of the Earth from the Sun: a fundamental astronomical measurement. The ’69 transit was the second of a pair, the first having been in 1761. Although observed from over 100 international sites by men of science from around the world, the 1761 observations had not been successful. The 1769 transit, then, would be the last chance to estimate the size of the solar system until 1874. The responsibility for planning, coordinating and commissioning Britain’s observations lay with the Royal Society.

A meeting of the Royal Society with Isaac Newton in the chair, by J. Quartley, 1883

A meeting of the Royal Society with Isaac Newton in the chair, by J. Quartley, 1883

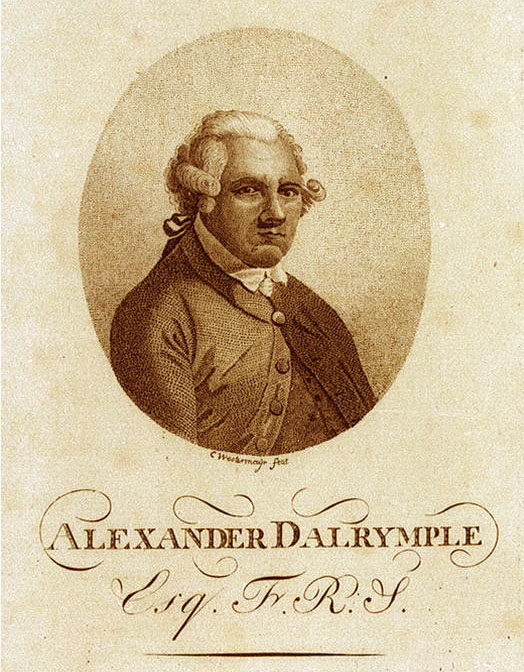

In November 1767, shortly before Cook arrived back in England from Newfoundland, the Royal Society had decided that in addition to the two observations being planned in the northern hemisphere – one at Fort Churchill in Hudson’s Bay and a second at North Cape, the northerly extreme of Norway ‒ a third observation point would need to be found in the South Pacific within what was described as a ‘cone of visibility’: that part of the ocean from which the transit could be seen. This was, in Pacific terms, a relatively small area that stretched for 3,000 miles west to east from Tonga to the Marquesan islands. Neither had been visited by Europeans for over a hundred years and there was, unsurprisingly, little faith in the accuracy of their reported positions. The Society discussed and interviewed a small number of people whom they thought qualified to observe the transits. Their favoured candidate for the Pacific observations was Alexander Dalrymple, an East India Company official, who impressed the Society’s selection committee as being “a proper person to send to the South Seas, having a particular Turn for Discoveries, and being an able Navigator, and well skilled in Observation”. Dalrymple had a single condition: that he would only accept the position if he had command of both the ship and the observation. Dalrymple was a knowledgeable geographer who had gained experience of surveying and charting in the East Indies, but has suffered at the hands of history, not always unfairly. No voice at the Society spoke against Dalrymple’s condition, or at least, none that was recorded. Behind his insistence on the command of the voyage lay his real interest, less astronomy than discovery, and specifically to search for the Southern Continent. This elusive geographical whimsy had been shown on maps and globes for centuries and its proponents – Dalrymple not least ‒ argued that it could be a huge, habitable, populous and commercially promising land waiting to be discovered in the southerly reaches of Pacific Ocean where few ships had ventured: potentially a great prize, and not quite as eccentric an idea as it might appear today.

Alexander Dalrymple, by Konrad Westermayr, 1801

Alexander Dalrymple, by Konrad Westermayr, 1801

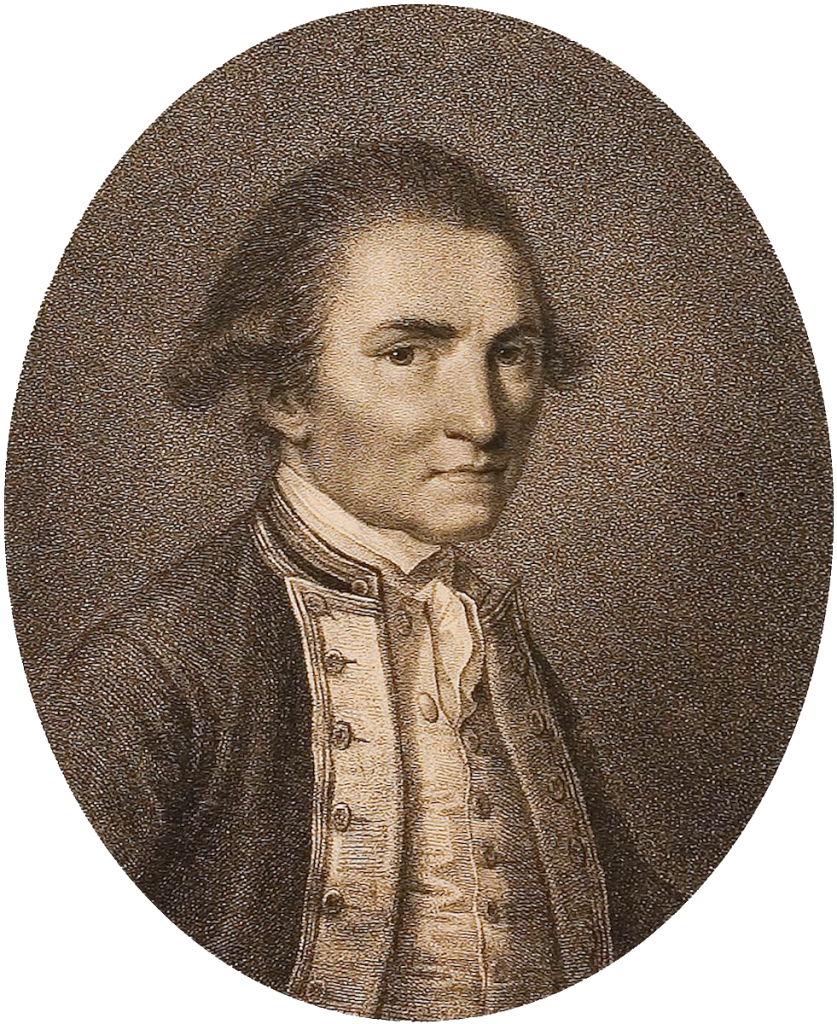

In January 1768, the Society – a well-respected but not well-heeled institution – asked George III for support for the observations, hearing on 29 February that the king would be pleased to grant £4000 and that the Navy would provide and outfit a ship. Matters were then able to move forward more purposefully. On 5 March the Admiralty instructed the Navy Board to find a suitable vessel and by 29 March it had found and examined three, finally purchasing the Whitby-built collier, Earl of Pembroke, for £2800. The cost of adapting it for exploration and replacing weak timbers and spars would eventually double the price. The ship was renamed, more appropriately, Endeavour and the Admiralty enquired of the Society the size of the observing party, and whether it had any particular instructions that it might wish to include in the commander’s orders. Clearly, the Admiralty saw this as a naval expedition and thus their business to select and brief the commander. The Society was now in an embarrassing position and the following day its president, the Earl of Morton, met with the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Hawke, effectively having to recommend Dalrymple for the command the Society had already offered him. Giving Morton no more quarter than he had the French fleet at the Battle of Quiberon Bay, Hawke bluntly refused even to consider passing command of a naval vessel to a civilian, no matter how well qualified. Dalrymple, his position as entrenched as Hawke’s, promptly and irrevocably withdrew from the expedition. Opinions differ on responsibility for the unfortunate chain of events, but Hawke’s reaction was undoubtedly influenced by two much earlier and disastrous decisions to appoint civilians to command navy ships on scientific work, which had ended in public recriminations, a court martial and a near mutiny. Although these events had happened many decades before, the Navy had a long memory. It seems likely that Hawke simply saw the voyage as an extension of the naval interest in the Pacific that re-emerged after the Seven Years’ War: two naval expeditions had set out in the previous four years to search for the Southern Continent. The first had failed to find anything and the most recent ‒ Samuel Wallis’s Dolphin and Philip Carteret’s Swallow ‒ had only set out in 1766 and had yet to return. It is only at this point, on 12 April 1768, that Cook’s name first appears in the record. The Board of Admiralty received a letter from Hugh Palliser asking that a replacement for Cook be appointed to ensure the completion of the Newfoundland survey, for he (Palliser) understood that Cook was to be employed elsewhere. Palliser got his replacement – Cook’s assistant surveyor, Michael Lane ‒ but no more is heard of Cook until 5 May when he is formally introduced to the Royal Society as the expedition’s commander. On 13 May he passed the navy’s lieutenants’ examination, it having been decided that the commander of such an important voyage would need to be a commissioned officer. Cook took formal command of Endeavour at Deptford on 25 May, some six weeks after the meeting of Hawke and Morton.

James Cook, engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi after John Webber, 1784

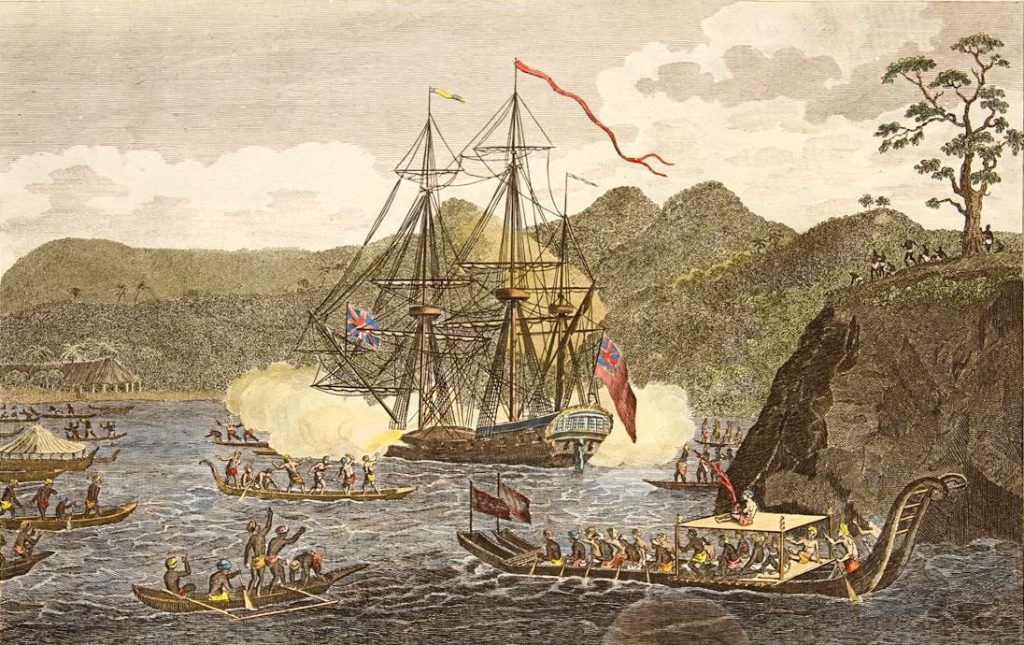

By a happy chance, Wallis’s Dolphin arrived back from its circumnavigation shortly before Endeavour’s departure with news that would shape Cook’s final instructions and, indeed, the history of the Pacific. In August 1767, Dolphin had landed at a large and populous island, one not before sighted by Europeans. Wallis christened it King George the Third’s Island. A few months later it would be visited by the French explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, who named it New Cytherea (after the Greek goddess for love) but neither name stuck and it soon became known round the world by its indigenous name, Tahiti. It was, it became clear on Dolphin’s return to Britain, sitting neatly within the ‘cone of visibility’, with a position that was accurately known. It was the ideal base from which to observe the transit. Furthermore, there were reports that some of the crew had even spotted the elusive Southern Continent below the horizon far to the south. Cook’s orders were adjusted accordingly to include a search once the observation was completed.

Attack on Captain Wallis in the Dolphin by the Natives of Otaheite (Anson 1784)

As a collier, Endeavour would have had a crew of between 12 and 15 men. For the Pacific voyage she was to be home to 70. Colliers were strongly-built, roomy ships for their size, capable of carrying a large crew and the vast range and quantity of stores that would be consumed on a long voyage. These included 7,860 pounds of sauerkraut (preserved boiled cabbage), one of a number of experimental foods being tested for their efficacy as a prevention or cure for scurvy, the ‘plague of the seas’ that could decimate a crew after a mere couple of months at sea. Endeavour also had to accommodate a range of astronomical and navigational instruments, for together with the observation of the transit of Venus and the surveys of new coasts and islands, the voyage was being used to test the accuracy of the lunar distance method finding one’s longitude (and so one’s position) at sea. The instruments included patent logs, octants, sextants, hand telescopes, astronomical telescopes, clocks, astronomical quadrants, transit instruments, artificial horizons, azimuth compasses, dipping needles, variation compasses, barometers, magnets, thermometers, water bottles (for taking deep-water samples), wind and tide gauges, globes and specialist books. All the instruments were hand-made by the finest craftsmen in London. The cost was staggering, but it is even more remarkable that the Admiralty was able to get them at all at such short notice. As if this wasn’t enough, the Admiralty agreed to accommodate a civilian scientific party led and paid by a wealthy young gentleman with a passion for botany, Sir Joseph Banks. Space had then to be found for a further nine people and an additional twenty tons of luggage. While Lord Hawke had to be persuaded of the value of a scientific party on the voyage (and one imagines that Cook, his officers and his crew might have shared his view), the natural historians, astronomers and artists would come to define scientific exploration in the age of the Enlightenment.

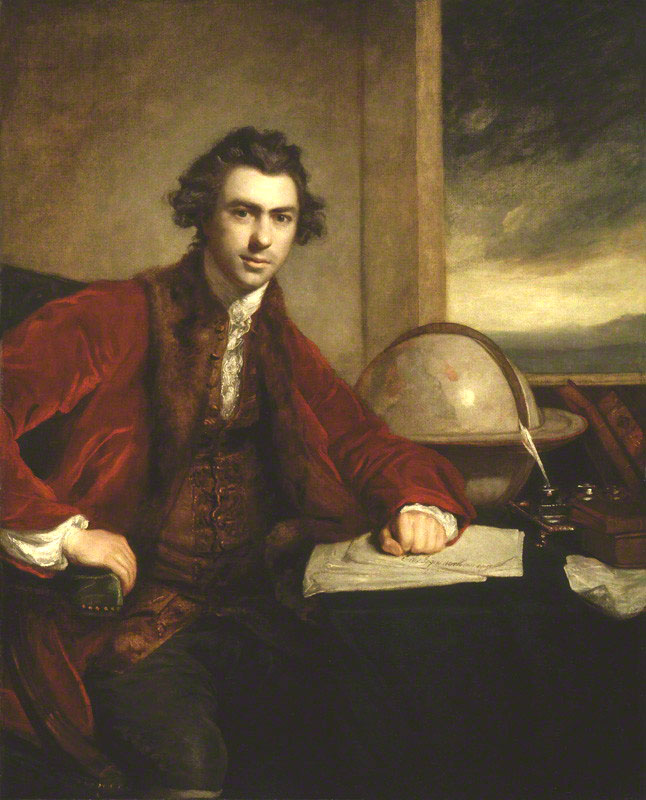

Sir Joseph Banks by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1773

Sir Joseph Banks by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1773

On 30 July, Cook received his final orders and Endeavour began to make its way down the Thames, anchoring off the Downs (the main anchorage at the mouth of the Thames) where Cook joined the ship, discharged the pilot and set sail for Plymouth. Here Banks joined them and on 25 August 1768 Endeavour embarked on a voyage that would last nearly three years.

Model of the Endeavour, © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (click to enlarge)

References:

J.C. Beaglehole, The Life of Captain James Cook, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1974

J.C. Beaglehole ed, The Journals of Captain James Cook on his Voyages of Discovery: Vol 1, The Voyage of the Endeavour, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999 (orig. Hakluyt Society, 1955)

Andrew S. Cook, ‘Alexander Dalrymple (1737-1808), Hydrographer to the East India Company and to the Admiralty as Publisher: A Catalogue of Books and Chart’. PhD thesis, University of St. Andrews, 1993. http://handle.net/10023/2634

Margarette Lincoln, Science and Exploration in the Pacific: European Voyages to the Southern Oceans in the 18th Century, Woodbridge and Greenwich: Boydell Press and the National Maritime Museum, 1998

John Robson, Captain Cook’s War & Peace: The Royal Navy Years, Barnsley: Seaforth, 2004 Glyndwr Williams, ed., Captain Cook: Explorations and Reassessments, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2000

Glyndwr Williams, Naturalists at Sea: Scientific Travellers from Dampier to Darwin, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013