Tuia – Encounters 250 commemorates the 250 years since the first onshore meetings between Māori and Pākehā in 1769–70. It also celebrates the voyaging heritage of Pacific people that led to the settlement of Aotearoa New Zealand many generations before. Use the links below to learn more about these aspects of New Zealand history, as well as access educational resources for teachers and parents.

Encounters in 1769

Learn about the first meetings and encounters between Māori and Pākehā on the NZ History website. Discover stories of encounter between two great voyaging traditions, Te Moana-nui-ā-Kiwa (Pacific) and European, which led to the formation of a new nation.

Te Moana-nui-ā-Kiwa

Te Moana-nui-ā-Kiwa, the Pacific Ocean, was one of the last areas of the earth to be explored and settled by human beings. It was only around 3000 years ago that people began heading eastwards from New Guinea and the Solomon Islands further into the Pacific.

Great skill and courage was needed to sail across vast stretches of open sea. Between 1100 and 800 BCE these voyagers spread to Fiji and West Polynesia, including Tonga and Samoa. Around 1000 years ago people began to inhabit the central East Polynesian archipelagos, settling the closest first.

The movement of peoples around the Pacific and from Asia into the Pacific over the last 6,000 years.

New Zealand was the last significant land mass outside the Arctic and Antarctic to be settled. The Polynesian culture emerged in Fiji, Samoa and Tonga from the earlier Lapita culture, which had formed from the mixing of the Melanesian peoples already living in Near Oceania with migrants from the vicinity of Taiwan. Around the end of the first millennium CE Polynesians sailed east into what is now French Polynesia, before migrating to the Marquesas and Hawaii, Rapa Nui/Easter Island and New Zealand, the far corners of the ‘Polynesian triangle’.

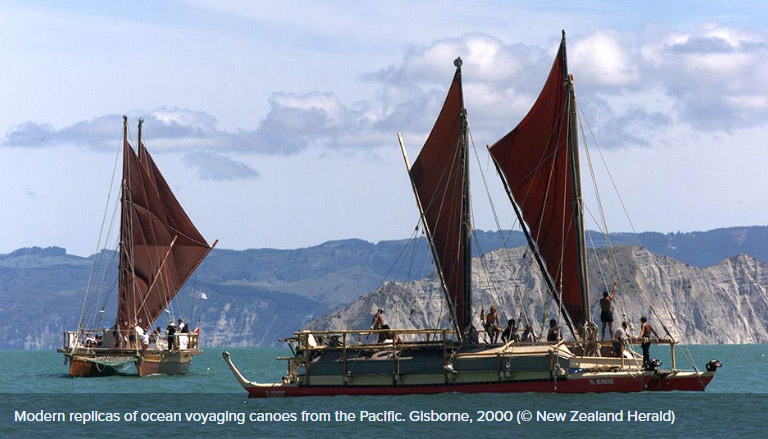

A broad range of evidence – including radiocarbon dating, analysis of pollen (which measures vegetation change) and volcanic ash, DNA evidence, genealogical dating and studies of animal extinction and decline – suggests that New Zealand’s first permanent settlements were established between 1250 and 1300. These migrants, who sailed in double-hulled canoes from East Polynesia (specifically the Society Islands, the southern Cook Islands and the Austral Islands in French Polynesia), were the ancestors of the Māori people.

Read more on New Zealand History website…

European Voyaging and Discovery

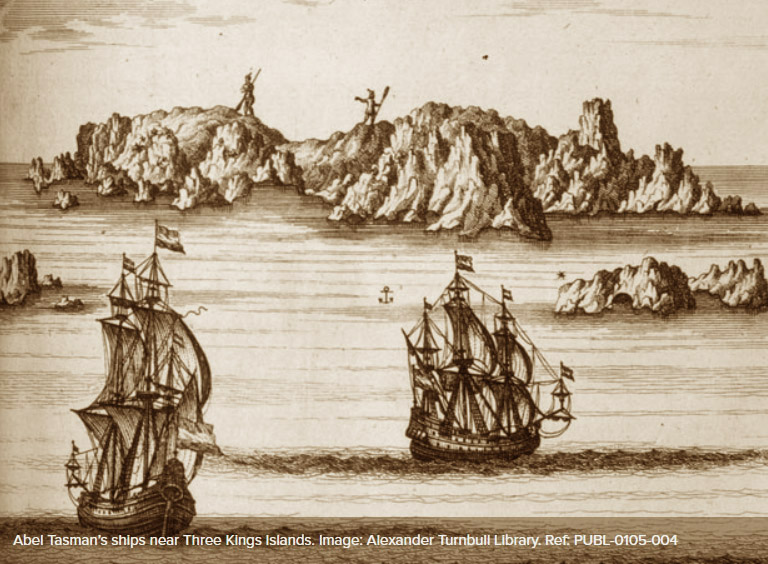

Portuguese and Spanish navigators sailed the Pacific Ocean in the 1500s, but there is no firm evidence that Europeans reached New Zealand before 1642. In that year the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman sailed in search of the vast continent which many Europeans thought might exist in the South Pacific. Dutch merchants hoped this land would offer new opportunities for trade. Tasman sighted New Zealand on 13 December 1642, but after a bloody encounter with Māori in what he called ‘Murderers’ Bay’ (now Golden Bay/Mohua) on the 19th, he left without going ashore. Tasman then sailed up the west coast of the North Island but did not establish how far east land extended.

John Byron’s voyage of 1764–66 is generally considered the beginning of serious English interest in the Pacific, which was encouraged by imperial rivalries with Spain, the Netherlands and France. In 1767 Samuel Wallis became the first European to visit Tahiti. By the time Wallis returned to England in May 1768, another expedition to the Pacific was already being organised. The Royal Society had proposed to the British Admiralty that the transit of Venus (the passage of the planet Venus across the face of the sun) be observed in the South Pacific. This observation, combined with others elsewhere, would make it possible to accurately calculate the distance from the Earth to both Venus and the sun. When Wallis returned with news of Tahiti, the expedition was instructed to go there to make the observations.

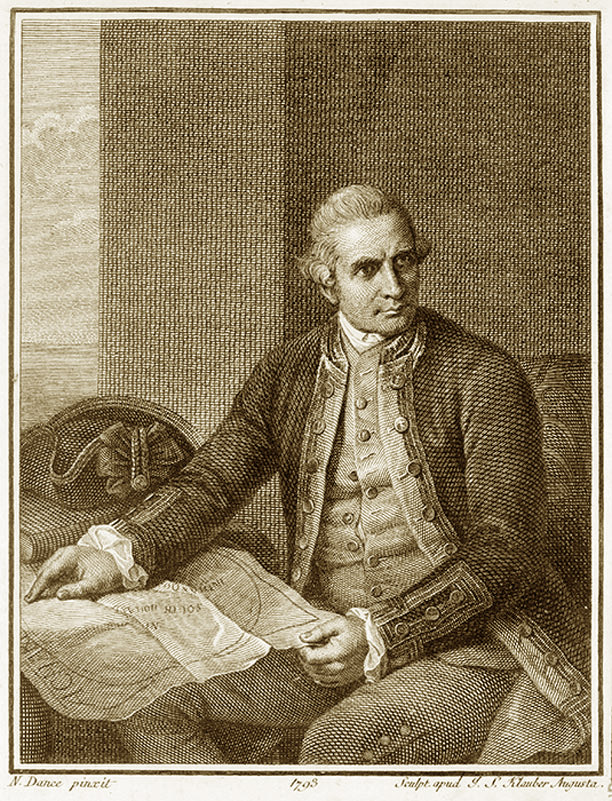

Lieutenant James Cook was appointed to command the expedition. Cook was approaching 40 and had 10 years’ experience in the Royal Navy, mostly in North American waters. Previous to the navy, Cook had worked in the coal trade, which turned out to be an advantage: the ship for the expedition was a former coal ship, a relatively small vessel of 368 tons, just 32 m long and 7.6 m broad.

Portrait of Lieutenant James Cook by Nathaniel Dance Holland

The ship, renamed Endeavour, departed from Plymouth on 26 August 1768 with 94 men aboard. After entering the Pacific around Cape Horn, it arrived in Tahiti on 13 April 1769 and spent almost four months there. One of Cook’s key companions was the gentleman naturalist Joseph Banks. Wealthy enough to indulge his interests, Banks paid for another botanist, the Swede Dr Daniel Solander, and three draughtsmen (artists) to join the expedition. Because of its scientific emphasis, Cook’s voyage has often been viewed more favourably than Tasman’s. However, the English, like the Dutch, also wished to expand trade and empire – the British Empire had political, strategic and economic expansion in its sights. Cook included in his reports information about the resources of the lands he visited, and the suitability of those lands for settlement by Britain.

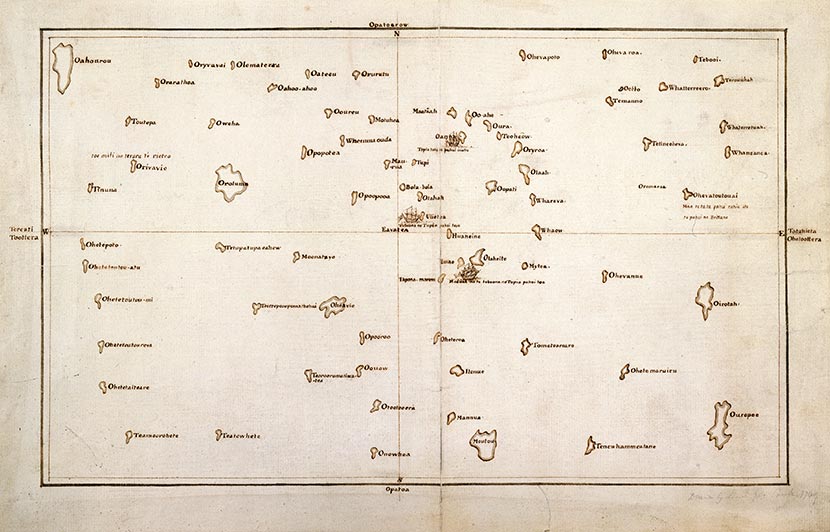

The third key figure aboard the Endeavour was Tupaia, a Tahitian arioi (high priest) who came on board at Tahiti. Until recent decades Tupaia’s crucial contribution has been largely invisible in accounts of Cook’s voyage. Tupaia was an expert navigator and helped Cook draw a chart showing the locations of more than 70 islands in relation to Tahiti.

Tupaia’s chart, 1769, demonstrating the vast knowledge of the South Pacific held by Polynesian voyagers

Once the planetary observations had been made, Cook’s expedition was to locate Tasman’s outline of New Zealand and establish how far it extended to the east. The Endeavour sailed south into uncharted waters and then west. On 6 October 1769, the surgeon’s boy sighted the high hills of Aotearoa.

According to some accounts, astonished Māori who saw the strange vessel from shore thought it was a floating island or the legendary bird Ruakapanga from Hawaiki. The people of Tūranganui-a-Kiwa were the first to meet Cook when he anchored. Conflict arose when the crew went ashore to seek water and supplies, and killed or wounded several Māori.

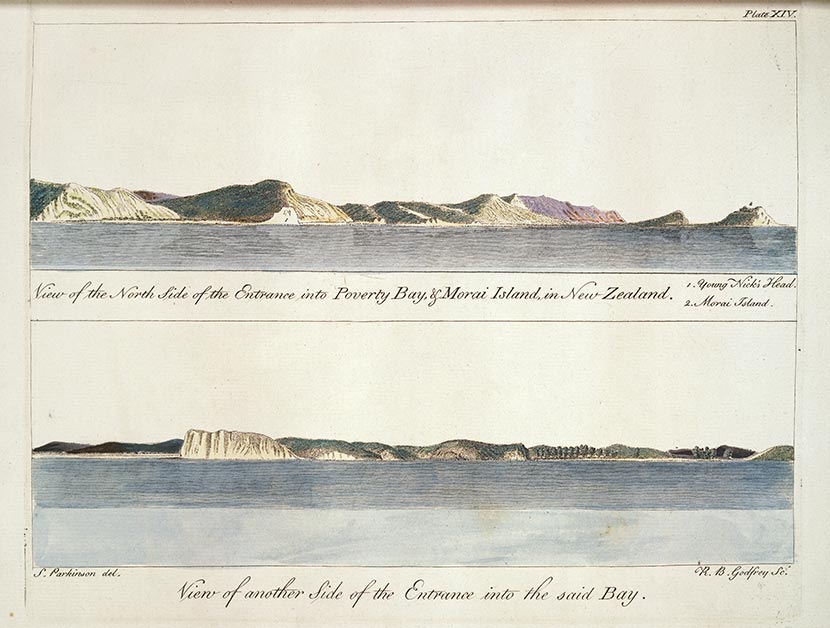

These engravings show the first part of Aotearoa seen by Cook and the crew of the Endeavour in October 1769 – Tūranganui-a-Kiwa, which Cook named Poverty Bay, including the headlands to the east of Gisborne city and Te Kurī-a-Pāoa, which Cook named Young Nicks Head after the ship’s surgeon’s boy who was the first to see land. They are based on drawings by Sydney Parkinson, the artist on Cook’s first voyage to New Zealand.

The Endeavour then sailed south, before returning to the north, travelling up around Cape Reinga and down the North Island’s west coast to Queen Charlotte Sound/Tōtaranui. Longer stops occurred at Uawa (Tolaga Bay), Te Whanganui-o-Hei (Mercury Bay) and Pēwhairangi (the Bay of Islands).

This engraving shows a fortified pā on top of an arched rock at Mercury Bay, on the Coromandel’s east coast, seen by Cook in 1769. The arch has since collapsed.

At Queen Charlotte Sound/Tōtaranui, Cook anchored at Meretoto/Ship Cove, a haven he returned to on each subsequent voyage. From a high point on Arapawa Island he first saw the narrow strait that now bears his name. Sailing through this strait, he sailed up the east coast of the North Island until he confirmed it was indeed an island, then down the east coast of the South Island and round the southern tip of Stewart Island/Rakiura.

Cook stayed at Meretoto/Ship Cove in Queen Charlotte Sound/Tōtaranui at the top of the South Island on each of his three journeys to New Zealand. John Webber, the official artist on Cook’s third voyage, painted Māori fishing there.

After restocking water and wood at Rangitoto ki te Tonga/D’Urville Island, Cook sailed west to chart the east coast of ‘New Holland’ (Australia) and called at the Dutch colony of Batavia (now Jakarta), where Tupaia died of illness. Cook arrived back in England, having circumnavigated the globe, on 13 July 1771.

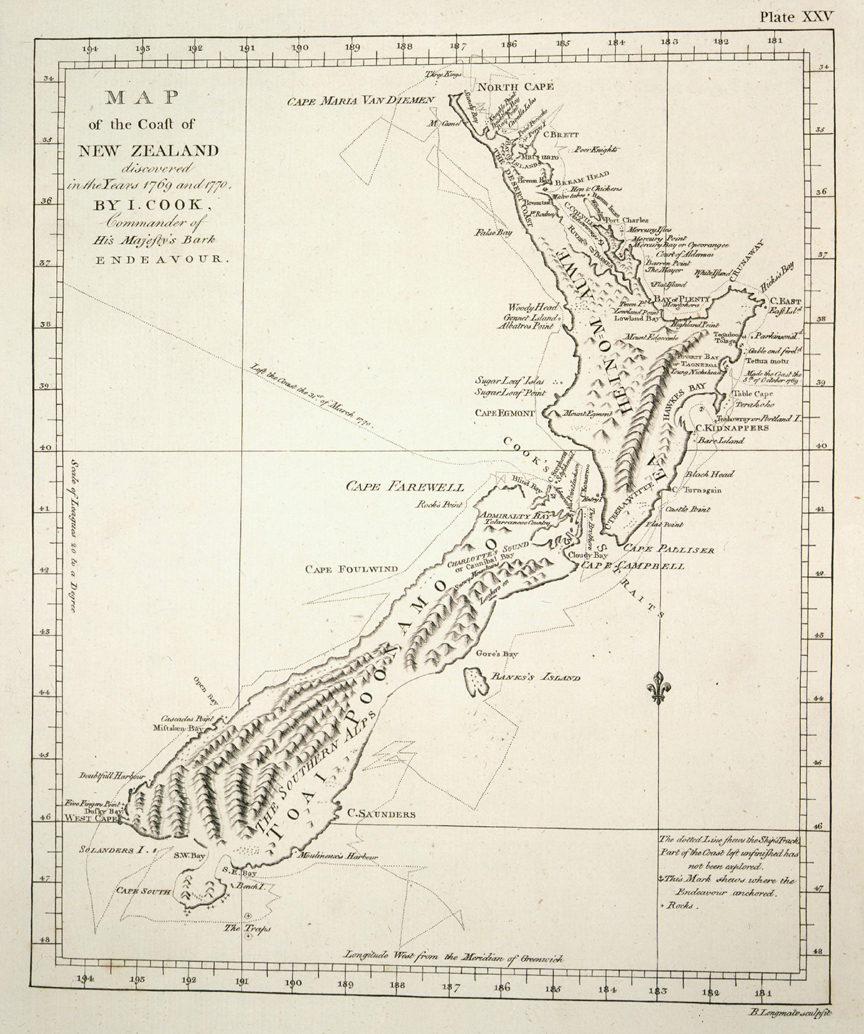

Drawn by James Cook in 1770, after his first journey, this chart of New Zealand was remarkably accurate and detailed. His precision and scientific approach set a new standard for the mapping work of the British Admiralty.

Read more on New Zealand History website…

Early Meetings Between Peoples

On the evening of 18 December 1642, two waka of Ngāti Tūmatakōkiri people approached two strange ships, which had anchored near the north-western tip of the South Island. These ships, the Heemskerck and the Zeehaen, were commanded by the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman. This was the first known occasion when Māori encountered Europeans.

The Māori group called out to the ships’ occupants and blew on a shell trumpet to challenge the intruders; the Dutch ship replied with their own trumpets. The next day, a waka approached with 13 Ngāti Tūmatakōkiri on board. They were shown gifts by Abel Tasman’s men, but returned to shore. Seven more craft then came out to the ships. A small Dutch boat, which was passing a message between the two ships, was rammed by one of the waka and its occupants attacked; four of the Dutchmen died. As the ships weighed anchor and set sail, 11 canoes approached and were fired on, possibly causing injuries. As a result of the incident, Tasman never landed on New Zealand shores, and named the place Moordenaars Baij (Murderers Bay).

This drawing, one of the very first European images of Māori, depicts Abel Tasman’s visit to Golden Bay/Mohua in December 1642. It is by Isaac Gilsemans, the artist on Abel Tasman’s voyage. In addition to the waka full of Māori men in the foreground, the image shows two incidents during the encounter: in the middle distance you can see Tasman’s two ships firing their cannon at the surrounding waka. In the left of the picture, the two ships can be seen leaving after the attack, with one of the small boats towing another.

James Cook

For almost 130 years, Europeans and Māori had no further contact with each other. Then on 8 October 1769, James Cook and others landed on the east side of the Tūranganui River, near present-day Gisborne. It appears from later accounts that the local Māori at first took the ship to be a floating island or giant bird. The fertile land surrounding the wide bay Tūranganui-a-Kiwa was home to a large population of Māori at that time, divided into four main tribes.

Cook’s relationship with Māori got off to a disastrous start when a Ngāti Oneone leader, Te Maro, was shot and killed by one of Cook’s men. It seems likely that the local people were undertaking a ceremonial challenge, but the Europeans believed themselves to be under attack.

When Cook returned to shore the next day a large group of Māori gathered. This time Cook had brought with him the Tahitian tahua (priest) Tupaia, who was able to converse with the Māori. A local man greeted Cook with a hongi, possibly on Toka-a-Taiau, a sacred rock in the Tūranganui River. As historian Anne Salmond observed, this would have been a ‘portentious, powerful place for the first formal meeting between a Maori and European’.

However, another fracas occurred in which the Rongowhakaata chief Te Rakau was killed by the Endeavour’s company, and others wounded. This time it seems likely that Māori were attempting to exchange weapons, but this was misunderstood. Later that day Endeavour crewmen attempted to seize the occupants of fishing waka, with the intention of taking them on board and gaining their friendship. Further Māori deaths occurred during this incident and three youths were taken captive; they were later returned to shore.

The replica of Cook’s Endeavour and the waka Te Awatea Hou – a waka taua built in 1990 – meet in Meretoto/Ship Cove in 1996, where Cook spent time on each of his journeys to New Zealand

Tupaia

During the first difficult days in Gisborne, another important moment of encounter took place, when the Tahitian tahua (priest) Tupaia came ashore from the Endeavour. Tupaia had been taken on board by Cook while in Tahiti and had proved himself a useful mediator between the Tahitians and the crew. Joseph Banks proposed that Tupaia and his servant Taiata come with them to England, and offered to pay for their passage.

Tupaia drew this image of Joseph Banks bartering with a Māori for a lobster during his journey around New Zealand on the Endeavour in 1769/70.

After the Endeavour’s arrival in New Zealand the decision to take Tuipaia on board proved to have been an inspired one when it became clear that he could communicate with Māori. Because the Māori language belonged to the Polynesian sub-family of languages, Tupaia, who had learnt some English, was able to translate spoken exchanges between European and Māori. He also recognised Māori customs and could discuss complex subjects with local people.

The Endeavour would afterwards be remembered by Māori as ‘Tupaia’s ship’. The Tahitian priest was to have more influence on the local people – who regarded him as a tohunga from Hawaiki – than Cook or any other individual on board.

As his biographer says:

in recognition of his prestige as a Tahitian tahua, Tupaia was greeted as an honoured guest, enfolded in valuable cloaks and entrusted with ancient treasures. Disassociated from the homeland for perhaps 500 years, elders, priests, chiefs and their people welcomed this heaven-sent chance to reclaim their ancient past.

Hundreds gathered to hear Tupaia preach, while priests engaged him in religious discussions. As the ship sailed north to the Bay of Islands, Tupaia was welcomed and feted: he was a valued interpreter and mediator for the Māori people, as well as for the Europeans.

Cook relied on Tupaia’s diplomacy to smooth relations with Māori. At Uawa (Tolaga Bay) the Tahitian conversed at length with a local tohunga and also sketched and painted.