In 1768, King George III and Britain’s Admiralty requested James Cook undertake two tasks on his expedition aboard the HMB Endeavour. First, to travel to Tahiti to observe the Transit of Venus, when the planet passes between the Earth and the sun. And second, to sail south in search of the fabled Terra Australis, which ultimately made them the first Europeans to visit eastern Australia.

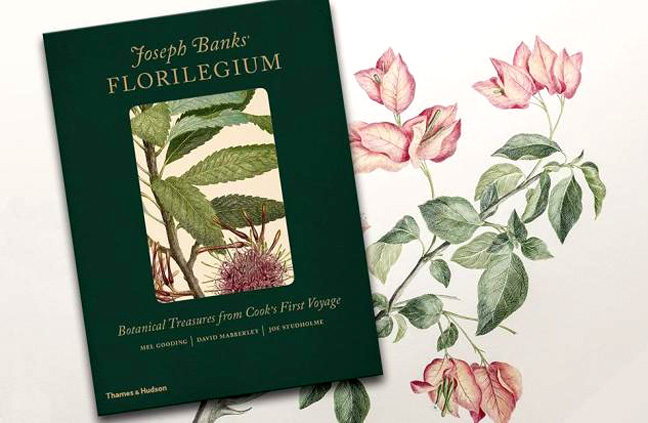

The voyage was largely funded by the 25-year-old Joseph Banks, a naturalist in possession of a healthy Age of Enlightenment curiosity. Banks was also in possession of quite a bit of wealth. “My grand Tour shall be around the whole globe,” he wrote of his 10,000-pound contribution to the voyage—a cool $2.3 million in today’s dollars.

by Sir Joshua Reynolds, oil on canvas, 1771-1773

Cook and Banks were joined by the botanical illustrator Sydney Parkinson, the Swedish botanist Daniel Solander and the astronomer Charles Green. With a library of more than 100 books and a mountain of equipment, HMB Endeavour set sail in August 1768. The assembled crew of specialists successfully recorded the Transit of Venus—a phenomenon that repeats every 243 years—on June 1769 and then turned towards Australia.

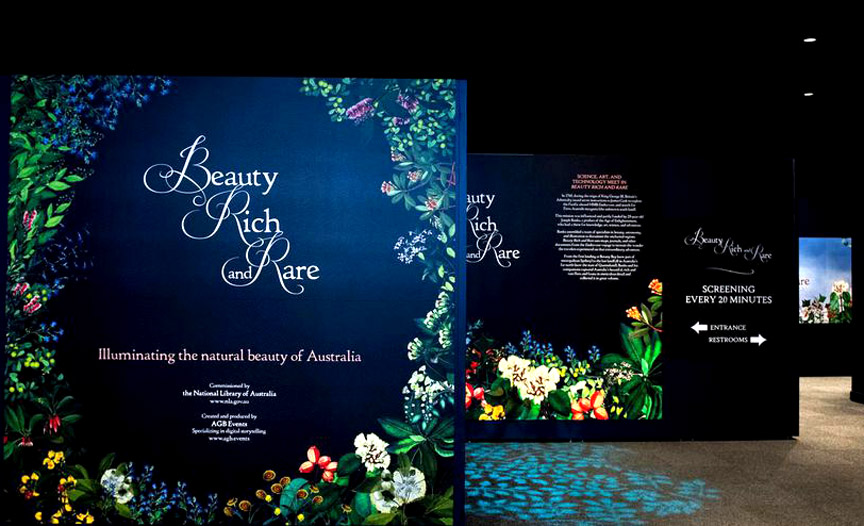

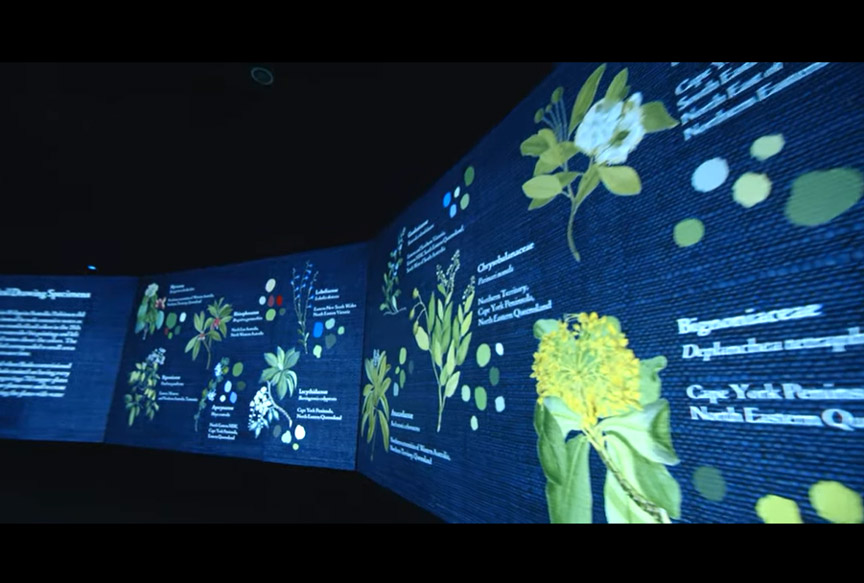

At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, vivid colors splash across a five-panel, 180-degree semi-circular screen, as enormous images bring to life Captain James Cook and Joseph Banks’ journey aboard the Endeavour. On view to mark the 250th anniversary of the expedition’s docking in today’s Botany Bay, is the 20-minute film Beauty Rich and Rare, a visual blend of science, art and technology, incorporating digital scans from Banks’ original floral sketches that are used to craft an animated time-lapse of the growth of many of the plants on the continent. The exhibition also features text from journals and publications documenting the original voyage and a selection of plant specimens that Banks brought back with him and are today held in the Smithsonian’s collections as part of the U.S. National herbarium.

The film—a work by AGB Events and the National Library of Australia, and sponsored by the Australian Embassy—treats visitors to the backstory of the thousands of species recorded by Banks and his team in their short stay. The immersive experience begins with a map of Australia featuring star patterns used by the country’s First Nations people, the world’s oldest continuous living culture, as watercolor drawings dissolve from one scene to the next. The film recreates the moment when Cook’s team first encountered and recorded Australia’s unique flora and fauna and how Banks’ rare collection of never-before-seen specimens paved the way for future herbariums around the globe.

“These collections really give us a snapshot in time of what life was like on the planet,” says W. John Kress, emeritus curator from the museum’s botany department. “Because this part of the world had been isolated evolutionarily for so long, there were a lot of exciting new things that were found.”

“Australia had not been connected to other land masses in a very long time,” says Robert Edwards, a postdoctoral associate from the University of Memphis who is conducting research at the Smithsonian. “We can never collect those [specimens] again, unless we get a time machine.”

This year as one of Australia’s worst fire seasons on record is slowly being contained after ravaging the country’s southeastern region with at least 27-million acres burned across New South Wales and Victoria, Banks’ collections have become even more critical for preserving and documenting the land’s ongoing change. Banks’ observations, his illustrations and his specimens, say Edwards and Kress, could provide a look into the history of life on the planet and its change over time. “These collections are going to help to document the decline in diversity. Then hopefully, it will allow us to document the increase of diversity on the other side,” Kress says, referring to the bottleneck effect, which is when a species goes through an event—climate change, natural disasters or even human activities—that reduces its population size.

The Journey to the “Unknown South Land”

On April 19, 1770, Zachary Hicks, Cook’s second in command, spotted land running from the northeast to the west. Nine days later, Banks and his crew docked in today’s Botany Bay—and were mesmerized by the flora and fauna dispersed around the region. Banks and Parkinson began recording in extensive notes their observations of the people, the language, the culture and the land.

“I therefore devoted this day to that business,” wrote Banks. “and carried all the drying paper ashore, and spreading them upon a sail in the sun, kept them in this manner exposed the whole day.”

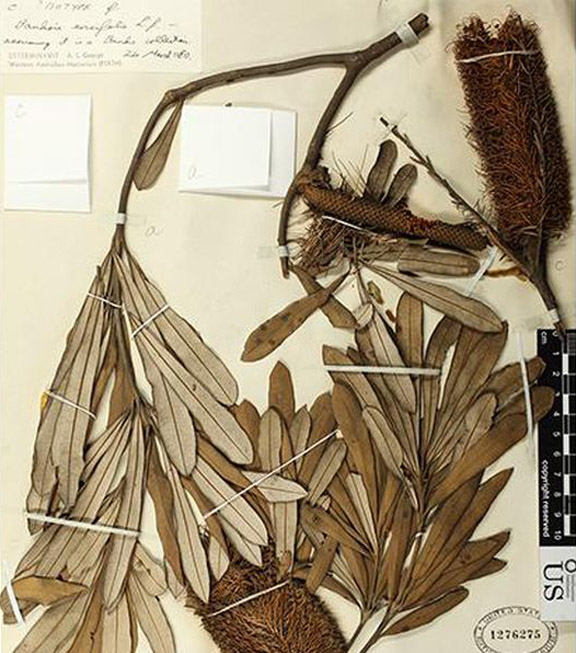

Banks recorded a wide range of specimens still observed today. He coined the word Banksia, for a large genus of plants that can grow sometimes as ground cover or as high as a tree, Edwards says, who is from Australia. In particular, Banks collected Banksia integrifolia, a woody, shrubby plant native to Eastern Australia. The species produces clusters of big flowers and vertical cones that rise up from the branches. Banksia is an integral part of Australia’s ecosystem, as animals rely on the plant’s structure for shelter and the nectar for food.

Banks also collected the Melaleuca quinquenervia and Melaleuca leucadendra, which are both members of the broad-leaved paperbark tree. With around 14 different, but closely related, species, the specimens are extremely difficult to tease apart, Edwards says. The plants have yellow-green sprays of flowers that are tightly packed together and resemble a bottlebrush cleaner, Edwards says. Because of its papery bark, Australia’s indigenous people could peel off its exterior into different shapes. This resource was used to create bags and even dress wounds, he says.

Banks was perhaps most fascinated by the kangaroo. “To compare it to any European animal would be impossible as it has not the least resemblance of anyone I have seen,” Banks wrote in his journal. “Its fore legs are extremely short and of no use to it in walking.”

In total, Banks and his team collected some 1,400 plant specimens to bring on their voyage back home. Banks and Parkinson added small sample patches of color to their sketches to later craft 743 full-color illustrations of the land’s plants and animals; Parkinson made 94 drawings in 48 days.

Banks and his team collected around 1,400 plant specimens, such as this Banksia integrifolia