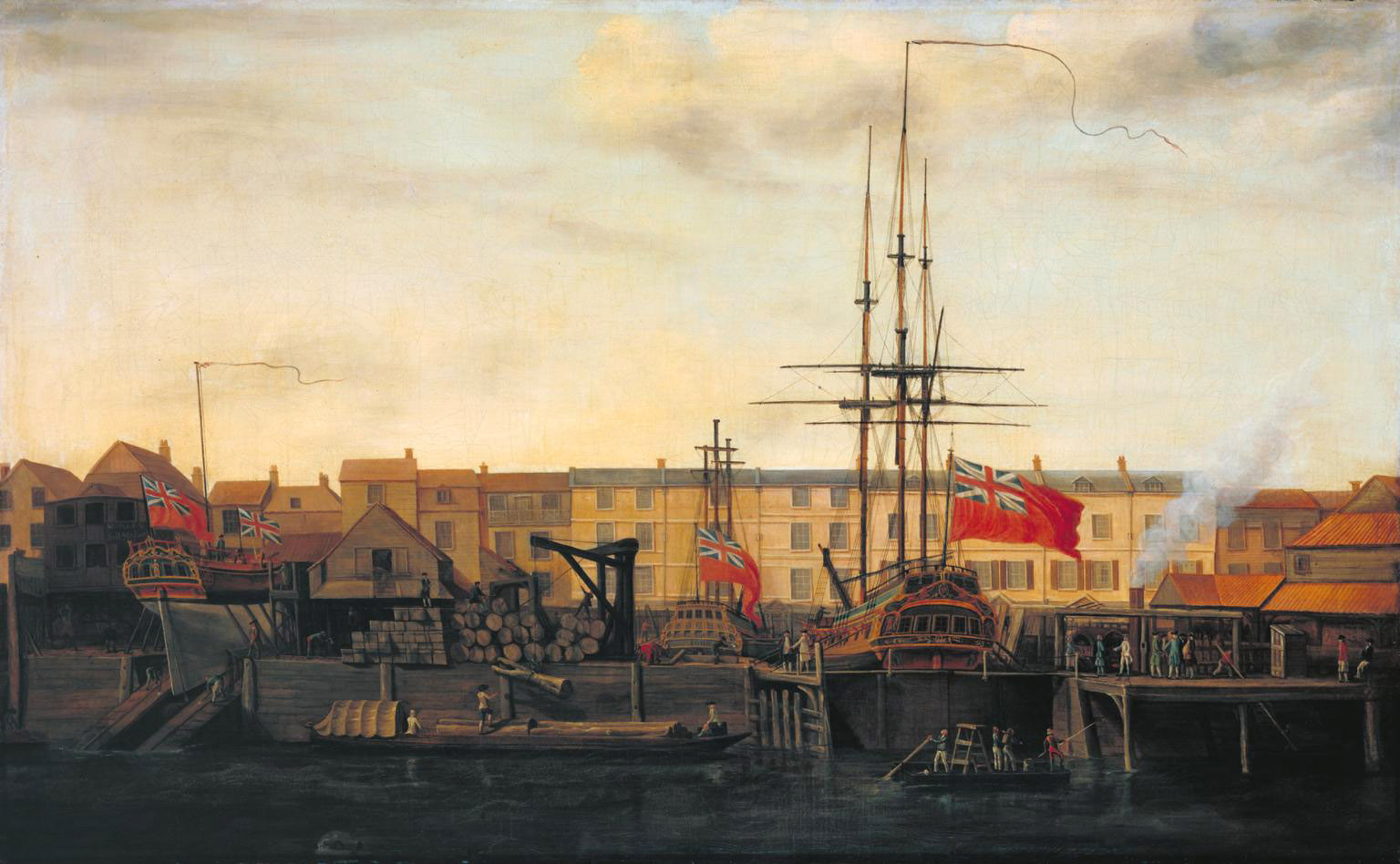

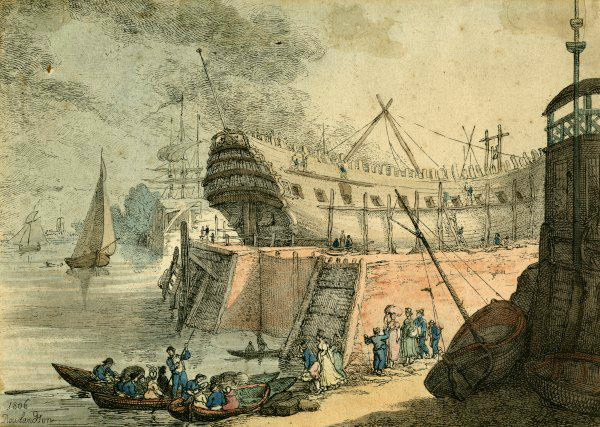

A Dockyard at Wapping, Francis Holman, c. 1780-4, Tate

Royal Navy (1755-1757)

The Navy, from J.C. Beaglehole’s The Life of CAPTAIN JAMES COOK

Cook volunteered at Wapping on 17 June 1755; and the only recorded reason is that he determined to ‘take his future fortune’ that way; or, much the same thing as recollected by Walker, ‘he had always an ambition to go into the Navy’. Among merchant seamen this was unusual. As between the two services there might seem to be no possible claim that the navy had on the rational man. If such a man, for his own purposes, wanted a different sort of ship from colliers, or a longer voyage than those of the coal or Baltic trades, he could join an Atlantic vessel, or enter the service of the East India Company. The disadvantage of that choice was that any seaman in the merchant service was in time of war subject to the depredations of the press gang, on shore or afloat, in his home port or as he finished a hard passage at Bombay or Calcutta.

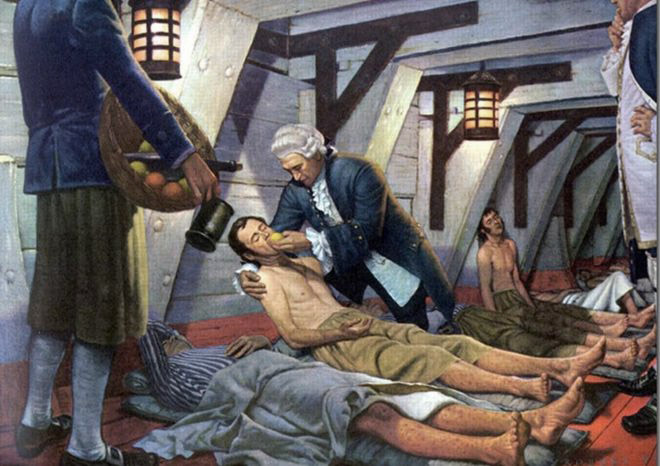

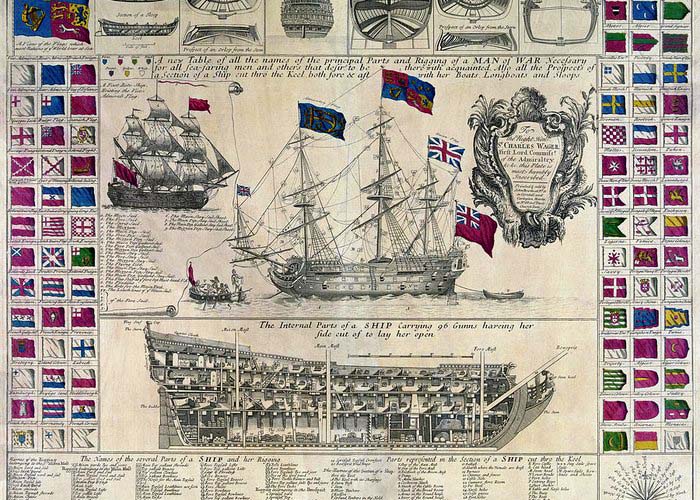

But there were years of peace as well as years of war; and in any case Cook, as the master of a merchant ship, could not have been pressed. We do not take at face value Dr Johnson’s reflections on the sailor’s life in general, that no man would be a sailor, who had contrivance enough to get himself into a jail; ‘for, being in a ship is being in a jail, with the chance of being drowned’. Men enough went to sea to give the lie to that remark; the merchant service at least was adequately manned. The navy was a different matter. Its physical conditions were worse; its pay was worse; its food was worse, its discipline was harsh, its record of sickness was appalling. To the chance of being drowned could be added the chance of being flogged, hanged or being shot, though it was true that deaths in battle were infinitely fewer than deaths from disease. The enemy might kill in tens, scurvy and typhus killed in tens of hundreds. ‘Manned by violence and maintained by cruelty’, as were the fleets of Britain to the mind of that great man Admiral Vernon (and his head on so many inn signs was an index to his dearness to the mind of the people), it is staggering to the mind of the historian that these fleets could attain a reasonable efficiency of movement and survival, quite apart from winning battles and wars.

Officers entered the navy voluntarily, from higher social classes, to make a career; but it was commonly thought in the profession that they should enter not later than their early adolescence, to be inured to its rigours soon enough for other modes of life to be deprived of attraction. A midshipman might do the duty of a seaman, and get a seaman’s pay, but he was a young gentleman, and aspired to become a lieutenant as soon as he had served the requisite term of years, and come of age, and passed his examination. He was in embryo a professional man. The ordinary seaman might be the scum of the dockyards, or an unfortunate landsman picked up by the press-gang, or something in between sent on board drunk by a crimp and unable to desert; the able seaman, however he got on board, and even if he had settled down to make the best of it, could hardly regard himself as a dedicated naval person, or his instincts as professional instincts. Men could be trained as seamen; they could, even under the conditions of the time, give loyalty and devotion to a good officer; a really good officer might even make a ship seem almost a humane place. The appearance of many men when they were first dragged on board a ship, however, might almost break an officer’s heart; and in spite of all the difficulties of bringing the navy from a peace footing to a war footing—raising its general complement, that is, from 16,000 to 80,000—there were numbers of miserable beings passed from ship to ship, unfortunates whom nobody wanted and the system yet could not bear to lose.

Typical 18th century sailors

In 1755 the navy was going on to a war footing. England and France were on the edge of world conflict, though each still preferred to maintain the fiction of peace, and in England there was a ‘hot press’. It brought in little of value, only ‘very indifferent landsmen’. The arrival of Cook at the Wapping rendezvous must therefore have been an agreeable incident in the day of the lieutenant in charge: a man young though mature enough, strong-faced, tall, well set-up, healthy, a seaman—and a volunteer, a prize indeed; with nothing against his intelligence, perhaps, except that he was a volunteer. The lieutenant must have looked at him with curiosity as well as gratification. Presumably, if Walker offered him the command of a ship, there must have been some correspondence between them, and to the respectable Quaker the step his protégé was taking can hardly have appeared proper or wise. No correspondence has survived. The £2 bounty can hardly have been an attraction to Cook, or the able seaman’s wage of £1 4s a month. There were precedents, though, few, that he might have heard of, of men rising from the lower to the quarter deck; but if that sort of ambition stirred in him, there is no evidence that he ever confided it in anyone. If he was finding the coasting trade dull, and thought that naval service, whatever its drawbacks, offered a lively mind more variety and more excitement, this was as good a time as any to make the change. We can henceforth follow his career a little more clearly. It is still, over a period, largely an anonymous career: not quite anonymous, because he was a man enrolled, we know where he was, and one or two things he did in the course of duty; but for the most part his personal history is subsumed in the history of a ship. We view his experience, we do not know what effect his experience had on him.

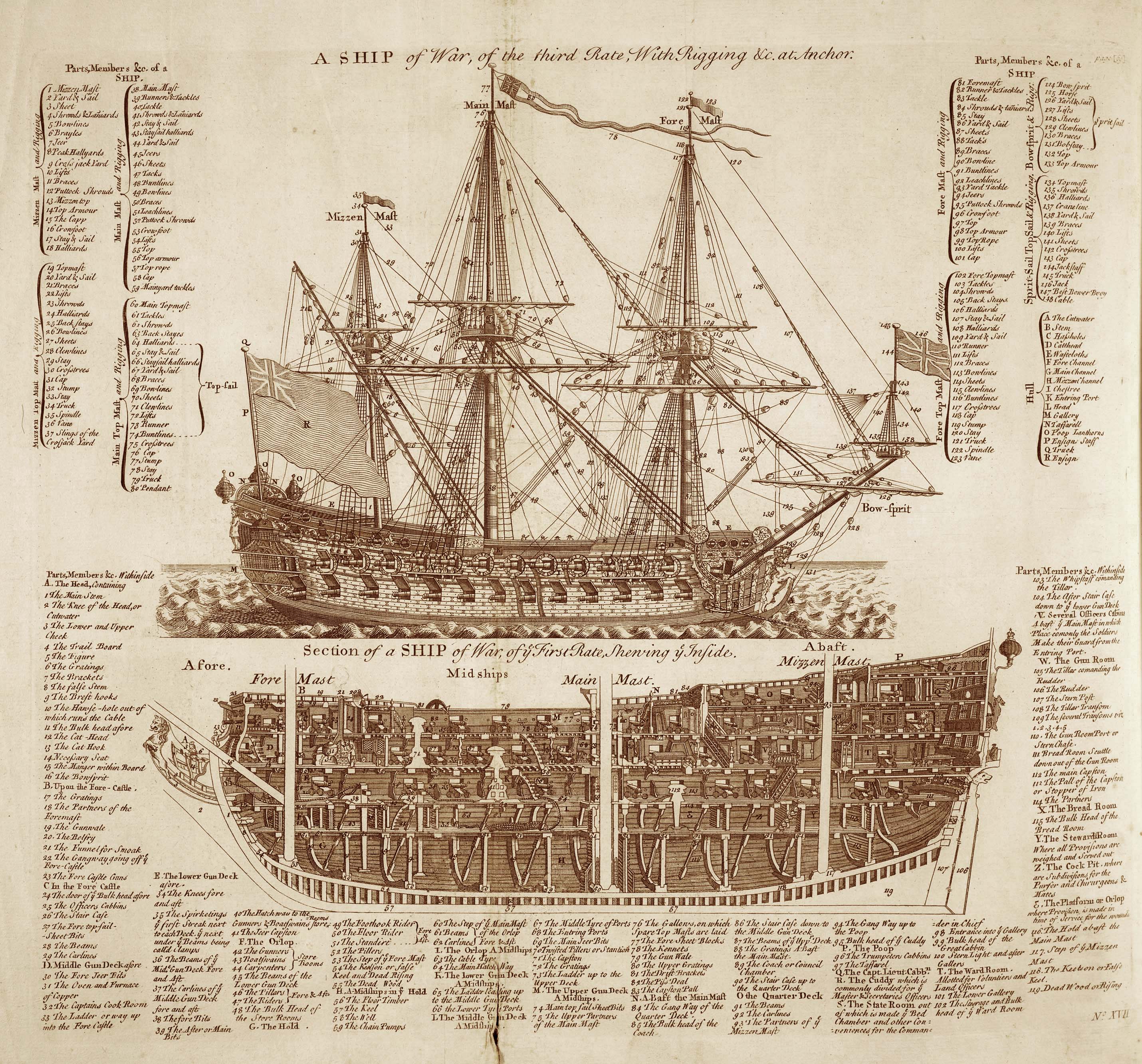

The volunteer was sent to the Eagle, Captain Joseph Hamar, a 60-gun ship then moored at Spithead. She had come out of dock in Portsmouth Harbour on 8 May, with only her lower masts and bowsprit standing, no rigging, and a vast deal to do to fit her for sea. There was still plenty to do when Cook made his first appearance in her, on 25 June. His appearance, we are to gather, was highly satisfactory to Captain Hamar, because a month later he was rated master’s mate. We have the log he dutifully began to keep, the first of many: ‘Log Book on Board his Majs Ship Eagle, Kept by Jams Cook Masters Mate Commencing the 27th June 1755; And Ending the 31st of December 1756’; and the first of innumerable entries registering wind and weather. The master was the very capable Thomas Bisset. Work on the ship went forward; at the beginning of July the fleet at Portsmouth was ceremonially visited by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Anson, and the Duke of Cumberland; ships and admirals came and went; the master’s mate recorded such happenings as ‘[20 July] Recd on Board 12 Chalder of Coals & 3 Cask’s of Char Coal, wth other Stoars for Pursser, Empd in Makeing Points & Pointing Ropes Ends’—or the arrival of ‘his Majs Ship Giberalter’; on 27 July all the volunteers on board got two months’ pay in advance; and at last, on 4 August, the Eagle sailed: ‘weigh’d & Came to Sail, Saw a water Spout to ye S.W.’ On that day too the mate, an incursion into the learned unusual among seamen, begins to use the astronomical symbols for the days of the week: he is already a slightly unusual young man.

Lord Anson, First Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty and Vice Admiral of Great Britain, after Reynolds, British Museum

The primary aim of the navy was the interruption of French communication with the possessions of France in North America, an aim in which it had so far not been markedly successful. The earlier intention for the Eagle was that she should cross the Atlantic to the Leeward Islands. In July, however, this plan was changed, and Hamar was ordered on a cruise outside St George’s Channel, between the Scilly Islands and Cape Clear on the Irish coast. He was to put himself under the command of Admiral Hawke. It was a cruise of no great glory. One day out a sail to the south was taken to be a French ship of war, and chased, but proved a Dutch merchantman. From day to day small vessels were chased, stopped and examined; and Hamar, short-handed as he was, did not miss the chance to press men when he could from the London-bound—three one day, four another. Half-way through August the weather turned squally. At the beginning of September there were hard gales; early in the morning of the 1st, off the Old Head of Kinsale ‘a Monstrous great Sea Carry’d away the Driver Boom in a deep Roll’, and a few hours later the captain was convinced his main mast was sprung between decks. He decided to go into Plymouth for repairs, and there he was anchored on 5 September. After two surveys in a week the mast-makers could find nothing wrong; and then Hamar, ordered to sea again immediately by an indignant Admiralty, and ready for sailing, decided instead to put his ship in dock to clean and tallow her bottom. This was too much for the Admiralty, who did not like its commands ignored, and before the end of the month Hamar was superseded. On 1 October came on board in his stead Captain Hugh Palliser. His arrival meant much more to Cook than either dreamed.

Palliser was another Yorkshireman, from the West Riding, well-rooted in the gentry; the son of an army captain. Five years older than Cook, he had had twenty years’ more naval experience: he had gone to sea at the age of twelve, in an uncle’s care, passed his examination and become a lieutenant when eighteen (which was three years too early for a commission according to the regulations), been in the action off Toulon in February 1744, and got his first command in 1746, the year in which Cook began as Walker’s apprentice. He had served in the West Indies and on the Coromandel coast of India as well as on the English coast, and in September 1755 had just returned from convoying transports out to Virginia. He was a capable man, although certainly never hindered in professional advancement, to his new command he brought a good deal of energy. He sailed from Plymouth in the Eagle for the first time on 8 October. The cruise this time was down Channel and about its western approaches, under the general orders of West and Byng, rear-admiral and vice-admiral; but for the greater part of five weeks the Eagle was on her own. They were weeks of gales and squalls, hard on the sails, and no doubt hard on the sailors, as the ship chased any-thing in sight—vessels which usually turned out to be English, Spanish, Swedes, Hamburgers or Dutch, though she took two or three French ones, fishermen homeward bound from Newfoundland. In one chase forty leagues west of Ushant, 18 October, in a hard gale, her main topmast went by the board and the Frenchman escaped under cover of night; but next day, with a jury topmast, the Eagle fell in with the Monmouth, and the Frenchman being sighted again, the Monmouth took her. The prizes were sent in to Plymouth. The Eagle, with more than two hundred prisoners, continued cruising, ran into gales again in early November, carried away her main topgallant mast in a squall, and on the 13th was with West and Byng in the Bay of Biscay.

Royal George at Deptford Showing Launch of The Cambridge, John Cleveley the Elder, 1757

She was present at the end of the Espérance, a French seventy-four short of fifty guns, which had eluded Boscawen’s fleet on the other side of the Atlantic only to be maimed in the storms and brought up by West’s squadron almost within reach of home: in a fight that for hopeless heroism was like that of the Revenge she was finally battered into surrender. She was to enter no British harbour as a prize, and Cook’s log registers her last hours, on the afternoon of the 15th: ‘Recd on Bd from ye Esperance 26 Prisoners art 4 ye Esperance on fire there being no Posabillity of Keeping her above water’. And so she went down. A few days after this funeral rite Byng, having returned to the Channel, ordered West and half-a-dozen ships, including the Eagle, into Plymouth Sound for cleaning and refitting; and here she remained from 21 November to 13 March 1756. On 27 November Palliser wrote to the Admiralty Secretary with the perennial captain’s plaint. He had a great many men on board, he said, who were supernumeraries belonging to other ships, and had been received at different times from them or from hospital, to make up a sufficient crew to go to sea. What ships they properly belonged to he could not tell, and nobody wanted them: forty-four were alleged to belong to the Ramillies, she needed only six, and her boatswain thought only three worth taking. ‘When their Lordships shall think proper to Compleat this Ships Complement I hope they’ll be pleased to Order her a few good Men, for I assure you I have been much distressed this last Cruize having so very few Seamen on board.‘ One of his best seamen, James Cook, in February spent a few days in hospital with an unspecified minor illness; some of the others were flogged round the fleet for desertion; otherwise (and even thus) it was the routine of winter weeks in harbour.

The winter, so it seems, was marked for Cook by further promotion. ‘AM had a Survey on Boatswain’s Stores, when Succeeded ye Former Boatswain’. This was on 22 January. It may have been only temporary. As boatswain he would have been responsible for ropes, sails, cables and anchors, flags, and (not unnaturally) boats; his pay would have risen from £3 16s to £4 a month. It was very satisfactory, though Palliser still refers to him as a mate, he continues to appear in other records as master’s mate, and as such he may continue to be referred to here.

She left again, her crew increased to 420, on 29 December—the blockade was winter work as well as summer—only to meet a very hard gale of wind off the Isle of Wight on 4 January 1757, ‘which blowed away most of our sails’, and forced her to put first into Spithead and then back to the Sound until 30 January, when she sailed with the fleet of Vice-Admiral West. This was a Biscayan cruise rather than an off-Channel one, and lasted till 15 April. Palliser was given fourteen days’ leave for ‘some business of consequence in town’ while the usual cleaning and refitting went on. On 25 May, in company with the Medway, another 60-gun ship, Captain Proby, she departed to rejoin Boscawen. Five days later she had her moment of glory. It was an Atlantic action, its place given by Palliser as about latitude 48° and 2° W of the Lizard—that is about 180 miles southwest of Ushant. At 1 o’clock in the morning, through driving rain, a sail was seen to the north-west of the two English ships. They immediately gave chase: ‘let out the Reefs, & set Studding Sails & Clear’d Ship for Action’, wrote Palliser in his log. The Medway, in the lead, omitted to clear for action, and was forced to bring to when nearly up with the chase to do so; by this time she had hoisted French colours. Proby, the senior captain, at first urged Palliser on, then wished him to shorten sail so that he himself might get into the action; Palliser, however, did not understand—possibly did not want to understand—the signals, and Proby managed only a few raking shots.

‘At 1/4 before 4’, writes Palliser, ‘Came along side the [chase] & Engaged at about Two Ships lengths from her the Fire was very brisk on both Sides for near an hour, she then Struck to us, She proved to be the Duc D’Acquitaine last from Lisbon, mounting 50 Guns all 18 Pounders, 493 Men, We had 7 men Killed in the Action & 32 Wounded, Our Sails & Rigging cutt almost all to Peices, soon after She Struck her Main & Mizen Masts went by the Board Employed the Boats fetching the Prisoners & carrying Men on board the Prize, Employed Knotting & Splicing the Rigging. Our Cutter was lost alongside the Prize by the going away of her Main Mast.’

At the end of the day the prize’s foremast also went by the board, and three of the Eagle’s men died of their wounds; another died two days later. Eighty (notwithstanding Palliser’s first count) were wounded. The French losses were fifty killed and thirty wounded. The Eagle herself had suffered badly, her masts and rigging and sails ‘very much shattered’, sails indeed ‘rent almost to rags’, almost all the running rigging shot away, her sides full of shot-holes, and stuck, like her masts and yards, with bars of iron. She was in no case to do much about her conquest, which the Medway took in tow. The latter had had only ten men injured from an accidental explosion of powder. The Duc d’Aquitaine was an East Indiaman of 1500 tons, commanded by ‘the Sieur D’Esquelen’; she had landed a rich cargo at Lisbon, whence she had sailed on her way round to Lorient, equipped for war and hoping to intercept a British convoy about to sail from Lisbon in charge of the 20-gun Mermaid, but before this desperate action had taken only an English brig from Cadiz. This the Sieur obligingly ransomed for £200, and let go.

The Battle of the First of June, 1794, by Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg, Royal Museums, Greenwich