This year marks the 250th anniversary of the first visit to New Zealand by Captain James Cook. Historians have covered his voyages in some detail with various opinions given on his suitability as an explorer, diplomat, sailor and navigator. Unfortunately history has not covered Cook’s skills as an astronomer particularly well so the importance of his observations of the transit of Venus in 1769 have often been overlooked. Cook and the crew of the Endeavour contributed to the measuring of one of the most important constants in astronomy, one that gave 18th century astronomers an understanding of the scale of the known universe. Until that time we had no idea how far the Sun was from the Earth, or the real distance to the other planets. Kepler and Newton had figured out the relative positions but we didn’t know the final piece of the puzzle that gave the universe scale. Cook’s observations at Point Venus in Tahiti in 1769 were critical to the calculation of the Astronomical Unit, the distance between the Earth and the Sun.

The journey to Tahiti was long and started well before acquisition of the bark Endeavour. It was the remarkable but very short career of Jeremiah Horrocks that gave attention to the transit of Venus across the face of the Sun which was very aptly described by Edmund Halley 77 years later:

“VENUS IS SELDOM SEEN WITHIN THE SUN’S DISC: AND DURING THE COURSE OF MORE THAN 120 YEARS, IT COULD BE SEEN ONCE; NAMELY, FROM THE YEAR 1639 (WHEN THIS MOST PLEASING SIGHT HAPPENED TO THAT EXCELLENT YOUTH HORROX OUR COUNTRYMAN, AND TO HIM ONLY; SINCE THE CREATION)”

Horrocks’ friend William Crabtree also witnessed the event and importantly, Horrocks was the only person to successfully predict the transit. Unfortunately Horrocks died at the young age of 22 and the world was never to know what amazing achievements that this great astronomer may have had. Halley was making the point that Horrocks, he forgot Crabtree, was the first person to observe a transit of Venus.

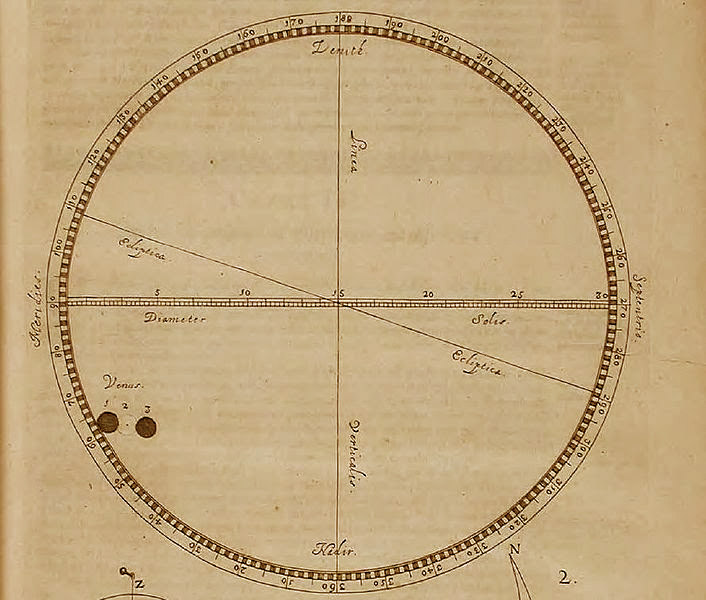

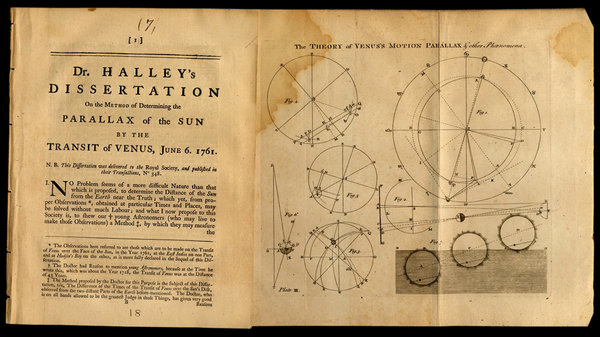

Fortunately, later in the 17th Century Edmund Halley picked up on the work of Horrocks and ultimately determined that the transit of Venus would be a useful method to calculate the distance between the Sun and the Earth. Halley spent some time on the Atlantic Island of St Helena and while there he observed a transit of Mercury. He noted that he was able to observe with the “greatest of accuracy” the moment that Mercury made second contact. This is the instant when the black disk of Mercury was immediately inside the Sun and the moment before light fully surrounds the planet’s image in the full Sun’s disk. He also observed how easy it was to measure the time of the transit across the Sun’s face and how this might be a method of calculating the Sun’s parallax which would directly lead to knowing the distance between the Earth and the Sun. Halley figured out that by recording the time it would take for Venus to cross the Sun’s disk from different places on Earth then the Sun’s parallax “may be determined, even to a small part of a second.”

Once armed with this knowledge Halley set about figuring out how this might be achieved and from where on the Earth’s surface would the next transit of Venus be best observed. The basic theory is that for two observers standing on the Earth, separated by a significant amount of latitude like one in the Northern Hemisphere and one in the Southern Hemisphere, then the lines that Venus tracks across the Sun’s face, made by the two different observers, will be displaced by some vertical distance. Unfortunately this vertical distance will be tiny and very difficult to measure, especially with the equipment available in the 17th century.

Halley figured out that you could get a result by comparing the times that the two transits would take and this time difference would be far easier to measure. The only negative was that an observer would be required to observe the full path of Venus across the Sun and be able to accurately measure that passage of time and this was no easy task. This required the transit to be visible for about 8 hours so location would need to be chosen that would see the transit during the day and hopefully not be cloudy. Halley also figured out some of the adjustments that would also need to be made to any determination of the parallax due to the rotation of the Earth.

by Richard Phillips, oil on canvas, feigned oval, 1721 or before

Halley determined that Hudson Bay would be an ideal spot to observe the transit in 1761. He also suggested Fort George in Madras and opined that the Dutch might like to take observations in Batavia (Djakarta), he seems he has a little dig at the Dutch:

“AS TO THE DUTCH, THEIR CELEBRATED MART AT BATAVIA WILL AFFORD THEM A PLACE OF OBSERVATION FIT ENOUGH FOR THIS PURPOSE, PROVIDED THEY ALSO HAVE BUT A DISPOSITION TO ASSIST IN ADVANCING, IN THIS PARTICULAR, THE KNOWLEDGE OF THE HEAVENS.”

Unfortunately for Halley he didn’t live to see the observations of 1761 but he left his successors with this challenge and rousing encouragement:

“I RECOMMEND IT THEREFORE, AGAIN AND AGAIN, TO THOSE CURIOUS ASTRONOMERS, WHO (WHEN I AM DEAD) WILL HAVE AN OPPORTUNITY OF OBSERVING THESE THINGS, THAT THEY WOULD REMEMBER THIS MY ADMONITION, AND DILIGENTLY APPLY THEMSELVES WITH ALL THEIR MIGHT TO THE MAKING THIS OBSERVATION: AND I EARNESTLY WISH THEM ALL IMAGINABLE SUCCESS; IN THE FIRST PLACE THAT THEY MAY NOT, BY THE UNSEASONABLE OBSCURITY OF A CLOUDY SKY, BE DEPRIVED OF THIS MOST DESIRABLE SIGHT; AND THEN, THAT HAVING ASCERTAINED WITH MORE EXACTNESS THE MAGNITUDES OF THE PLANETARY ORBITS, IT MAY REDOUND TO THEIR IMMORTAL FAME AND GLORY.”

Halley’s call to action was successful and it led to both transits in 1761 and 1769 being observed across the the globe despite the perils of long sea voyages, war and bad weather. The 1761 observations are tales full of courage, despair and bad luck but the lessons from that first round set the 1769 observations up to be more successful including William Wales’ trip to Hudson Bay and James Cook’s trip to Tahiti.

Notes:

The quotes in this come from the English translation of Edmund Halley’s: Methodus Singularis Qua Solis Parallaxis Sive Distantia a Terra, ope Veneris intra Solem Conspiciendoe, Tuto Determinari Poterit: Proposita Coram Regia Societate ab Edm. Halleio, in Philosophical Transactions, Vol 29, 1714-1716. He wrote it in Latin as he wanted the widest possible promulgation to get astronomers all over Europe enthused about the coming transit at the end of the century.

The translation was in Article 6 of James Ferguson’s 1761, A Plain Method of Determining the Parallax of Venus, by Her Transit Over the Sun; and From Thence, by analogy, The Parallax and Distance of the Sun, and of All the Rest of the Planets. Halley’s explanation of the mathematics left quite a few gaps which other astronomers tried to fill in over the years, including Ferguson, with varying degrees of success.

Read @SPACE_SAMUEL’s story on Milky-Way.Kiwi website.