By Emily Osterloff

Swedish naturalist Daniel Solander published little in his lifetime. But through his botanic collections from his travels and a rigorous application of a revolutionary naming system, he laid important foundations in taxonomy for scientists today.

A lithograph of Daniel Solander by Miss J Turner. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection

Born in Piteå, northern Sweden, naturalist Daniel Solander (1733-1782) is primarily remembered for his scientific contributions during James Cook’s first voyage.

Solander was invited aboard the expedition by friend and fellow naturalist Joseph Banks. The pair spent their round-the-world travels aboard HMS Endeavour (also known as HM Bark Endeavour) collecting and classifying thousands of plant and animal specimens.

Revolutionising Taxonomy

Daniel Solander’s interest in the natural world was ignited when he enrolled at Sweden’s Uppsala University in 1750. He initially studied law but abandoned the subject after becoming inspired by botany professor Carl Linnaeus, a scientist now referred to as the father of modern taxonomy.

Numerous discoveries of new plants and animals were being made at the time, increasing Western scientific knowledge. These finds were aided by Linnaeus’s new binomial nomenclature, a system of scientific names composed of two grammatically Latin parts. This taxonomic practice is still in use today.

The Linnaean naming system comprises two grammatically Latin parts, for example Blandforida nobilis [pictured], commonly known as Christmas bells. This image was drawn by Sydney Parkinson – who was also aboard HMS Endeavour – based on a specimen collected by Solander and Banks in Australia’s Botany Bay during the expedition.

Solander learned and mastered Linnaeus’s new naming system. Scientists elsewhere in the world were keen to apply it too, so in 1759 the professor sent his protégé to England as an emissary.

Although he initially intended to complete his doctorate at Uppsala, Solander never returned to Sweden. In 1762 he was appointed Assistant Librarian at the British Museum, cataloguing the natural history collections. These would become some of the founding collections of the Natural History Museum, over a century later. His work allowed him to further promote the Linnaean system.

Post-Endeavour, in 1773, Solander returned to the British Museum as Assistant Keeper. He continued to work with the collections until his death in 1782.

But it was a pivotal moment in 1764 when the botanist met landowner Joseph Banks, with whom he became a close friend and colleague.

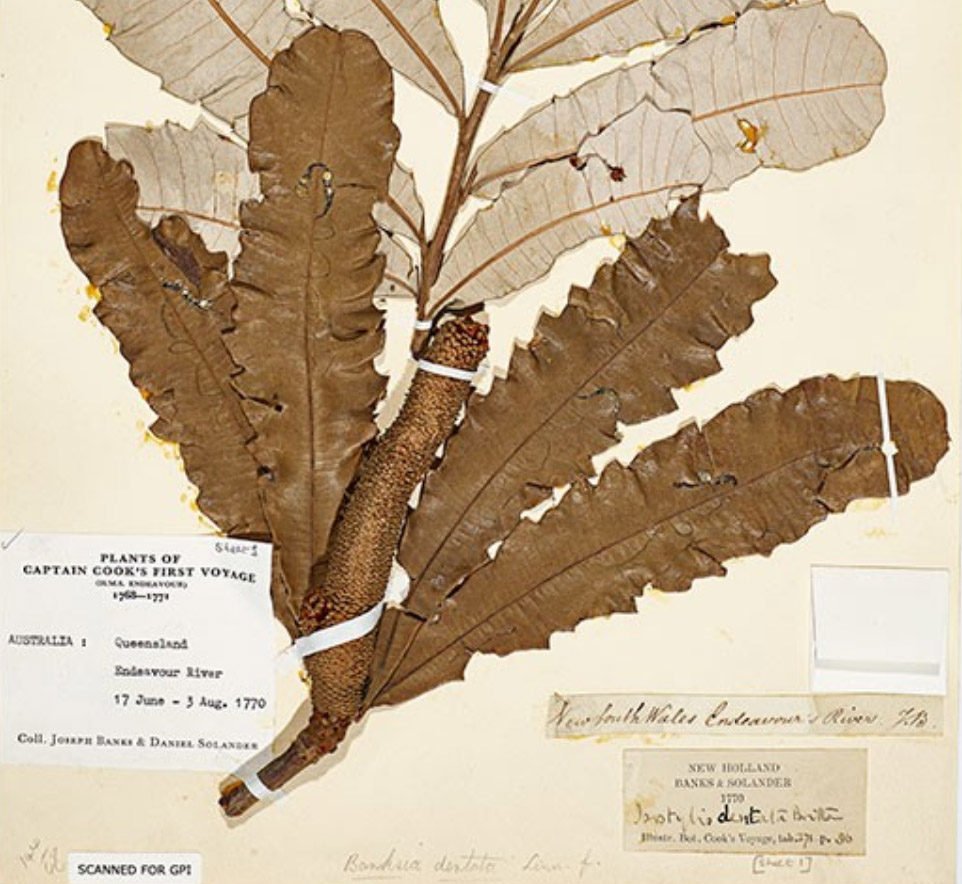

Banks and Solander collected around 30,000 specimens from 1768 to 1771, during their voyage on HMS Endeavour. The scientists took this sample of tropical banksia (Banksia dentata) from the Endeavour River in Australia.

Observing a Planetary Transit

Influenced by Solander, Banks had planned to study with Linnaeus at Uppsala. But he ultimately joined James Cook aboard HMS Endeavour, departing for Tahiti in 1768, and invited Solander to accompany him. The two scientists spent the expedition studying the natural history of the areas they visited.

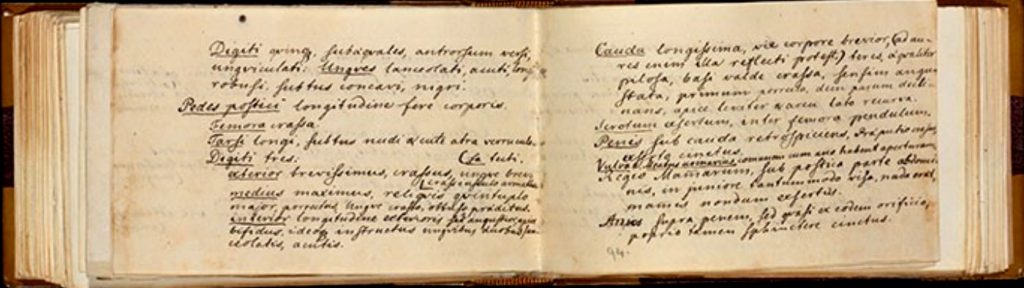

Solander was meticulous in his work categorising the specimens he and Banks collected, writing notes on the eponymous Solander slips – there are thousands of these sheets now bound together in the Museum’s collection. Those pictured above detail mammals found during the Endeavour voyage.

Leaving Plymouth in August 1768, the ship crossed the Atlantic, visiting Madeira and South America. Passing around Cape Horn (southern Chile), Endeavour sailed across the Pacific and reached French Polynesia in April 1769.

At anchor, Banks and Solander spent as much time as possible ashore, exploring and collecting almost every day. They would hastily describe their findings, while their artists sketched and painted them. While on passages with no new specimens, the naturalists would turn their attention to writing more detailed descriptions of their earlier discoveries.

Banks and Solander collected this specimen of St Helena ebony (Trochetiopsis melanoxylon) during the final leg of the Endeavour voyage in 1771 – it is labelled here as the synonym Pentapetes melanoxylon. This species is now extinct in the wild.

In June 1769, the scientists, led by astronomer Charles Green, made their observation of the transit of Venus from Tahiti Nui in the South Pacific. Prior to the trip, Banks had invested around £10,000 on equipment for his retinue. This allowed Solander a larger and clearer sighting of Venus than with supplies provided by the British government.

Brushes with disaster

Following the planetary transit, Endeavour cruised around the Society Islands for a month before arriving in New Zealand in October 1769. With enough gear and supplies for an extended exploratory trip, Cook sailed onwards to Australia, first sighting land on 9 April 1770.

The journey back to England took the ship via southeast Asia, South Africa and St Helena before making port in Dover in July 1771, having completed a full circumnavigation of the planet.

Sydney Parkinson’s illustration of HMS Endeavour beached for repairs on the bank of Australia’s Endeavour River after taking damage crossing the Great Barrier Reef. Image courtesy of State Library of Queensland.

Solander was met with many challenges in cataloguing the natural world during the voyage. On two occasions HMS Endeavour was almost lost in collision with coral walls of the uncharted Great Barrier Reef, and he had a number of brushes with death. While collecting Alpine flora in cold, snowy Tierra del Fuego (South America’s southernmost tip) in January 1769, he collapsed and had to be helped to the campsite. Two members of the Endeavour company died that night, including Banks’s secretary Thomas Richmond.

Between 1730 and 1752, Batavia, Java, would have over 1,100,000 deaths in a town of 2,500 houses at most. When Endeavour anchored there in October 1770, the ship’s two-month stay was marred by disease. Many of the crew contracted malaria, including Solander.

Journal entries from the passage to Cape Town chronicled the names of the many men who died of the ‘bloody flux’, known today as dysentery. Solander and Banks lost three of their party to the infection: Sydney Parkinson, John Reynolds and Herman Spöring Jr. Solander survived and was confined to his room for two weeks in South Africa. Despite this, Solander managed to classify 369 plants during his stay.

Solander’s Scientific Legacy

On their return to England, the two scientists received a mostly enthusiastic reception. By the end of the voyage, they had collected about 30,000 specimens, including around 1,300 species new to Western science.

The voyage was initially referred to by the press as the Banks and Solander expeditions – Cook was at the time still relatively unknown and went unnamed in a number of articles on the voyage.

A line engraving of Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander (1778). Although Solander never completed his doctorate in Sweden, he was presented with an honorary degree of doctor of civil law by King George III in 1771. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

In the post-Endeavour years, Solander became Banks’s assistant and librarian, cataloguing and researching the large collection kept at Banks’s home. He also continued his work at the British Museum.

The pair initially intended to join Cook’s second voyage, but Banks’s disagreements with the Admiralty over his demands ended their involvement. Instead, in 1772 Banks and Solander ventured to Iceland and the Outer Hebrides, and as with the Endeavour voyage, collected a number of botanic specimens.

To help preserve his manuscripts during his voyages, the Swedish naturalist invented the eponymous Solander box. This protective case is sometimes still used in libraries and archives.

Solander died on 13 May 1782 at Banks’s home from a cerebral haemorrhage. He was buried in the Swedish Church in Prince’s Square in Wapping, London. When the church was demolished in the early 1900s, the botanist’s remains were reinterred in the Brookwood Cemetery in Woking.

A plate depicting blue morning glory (Ipomoea indica) from Banks’ Florilegium. A specimen of this plant was collected by Banks and Solander between June and August 1770. This print is derived from an original illustration by Sydney Parkinson.

Banks and Solander had plans to publish the results of their Endeavour voyage. Over 700 printing plates were engraved and Latin descriptions had been prepared, however the work wasn’t completed before Solander’s death.

From the collections of their Icelandic expedition, again nothing was published by the two scientists before they died.

Banks invited other scientists to study the materials they had collected, and over a number of years scientific work using them was published.

After Banks’ death the natural history illustrations and specimens eventually came to the British Museum. Banks, Solander and their artists’ work was finally published in the 1980s in the 34-volume Banks’ Florilegium – over 200 years after the expedition.

The genus Solandra in the nightshade family Solanaceae was named after Daniel Solander. Pictured here is a flower of Solandra grandiflora.

Daniel Solander is commemorated in a number of ways, including New Zealand’s Solander Islands, Cape Solander in Australia and the genus of flowering plant Solandra.

In 2017 a new garden was named in his honour at the Swedish Embassy in Canberra, Australia. It features a number of the plant species he and Banks collected and studied when they visited the country in 1770.

View this story of Daniel Solander on the Natural History Museum website.