The three voyages James Cook led to the Pacific between 1768 and 1779 were extraordinary. On the first, the Endeavour voyage, Cook observed the Transit of Venus at Tahiti, completed the map of New Zealand and mapped the east coast of Australia. On the second, he proved that there was no great southern land. On the third, he attempted to find the fabled north-west passage from the Pacific to the Atlantic. His were the first European ships to reach Hawaii, where he and others were killed on Valentine’s Day 1779.

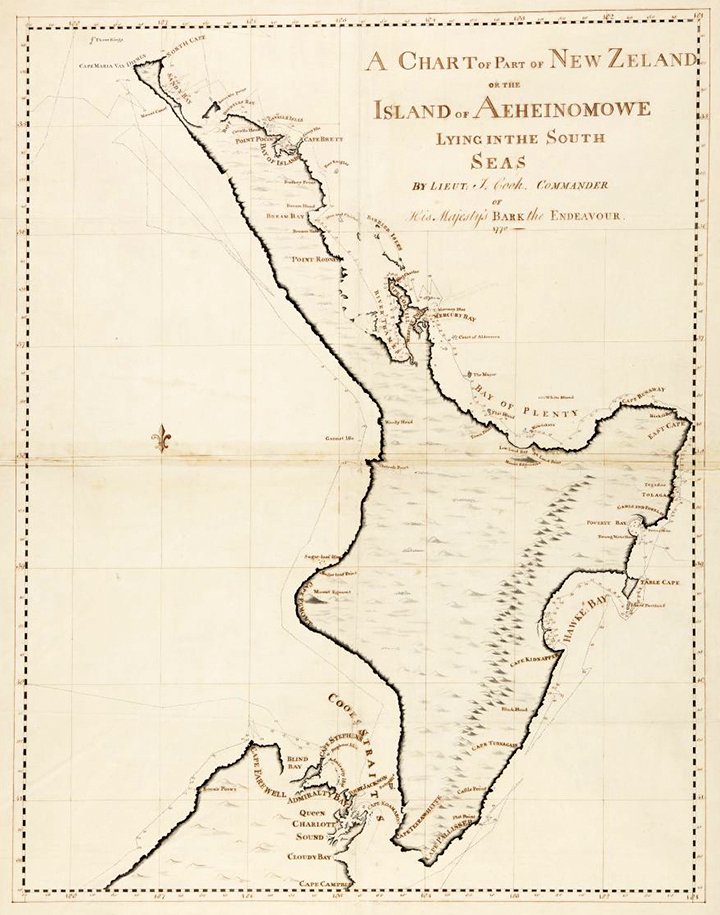

James Cook and Isaac Smith, A Chart of Part of New Zealand or the Island of Aeheinomowe Lying in the South Seas, 1770, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, SAFE/DLSPENCER 166 A

Over these three voyages for the Royal Navy, Cook’s converted Whitby colliers—the Endeavour, Adventure, Resolution and Discovery—made landfall in countless places. The men aboard these ships traded for supplies, collected botanical and zoological specimens and cultural objects, and documented landscapes they saw and people they met. It is no surprise that Cook’s are among the most documented and studied voyages in world history. Cook and those who sailed with him met a vast array of people of the Pacific. These meetings changed people on both sides, with lasting consequences.

His voyages unlocked the Pacific for Europeans. Though Europeans had long visited the Pacific, they had had unreliable maps. Cook’s improved maps, and the collections and accounts made on his voyages, opened doors that could never be closed. The relationships formed between peoples of the Pacific and the Europeans also changed Pacific politics, society, technology and health. Europeans brought exotic technologies, such as metal tools, and western diseases, and disrupted the dynamics of Pacific domestic politics and life.

In 2018, 250 years on from the Endeavour’s departure from Plymouth, it feels right to revisit Cook’s legacy, but with fresh eyes looking through different lenses. Over time, Cook has become a symbol, as much myth as man. Why? The National Library of Australia has long had a strong collecting interest in Cook’s voyages, offering rich pickings to investigate these questions. Yet Cook and the Pacific is its first full-scale, international exhibition about Cook.

Cook and the Pacific explores Cook’s Pacific voyages as meetings of peoples and their knowledge systems, of places experienced, cultures shared and exchanges made. It brings to the fore the stories of the many people and voices of the voyages from both ship and shore, both direct and mediated. There are records of relationships between people, of friendships, misunderstandings and instances of violence. Accounts of extraordinary conversations, exchanges and characters also survive.

Tupaia, Australian Aboriginal People in Bark Canoes, 1770, British Library, London, Add MS 15508, f.10, © British Library Board

Many of the people, objects and works of art featured in the exhibition are known from the detailed journals of Cook and the men who sailed with him. People are not just names on a page, but characters with known appearances and histories. Objects have uses and significance. Along with accounts, they also continue to resonate with First Nations communities visited by Cook. For many, their way of life, language and culture were changed forever as a consequence of the age of colonialism and cultural dispossession that Cook’s voyages prefigured.

The exhibition brings together some of the best Cook material from around Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Hawaii. The Library’s collections, both their strengths and their gaps, inspired what we sought to borrow from other collections. Together, the items on display tell stories not only of events as they were experienced at the time, but also how the voyages have been remembered and reinterpreted.

Highlights among an embarrassment of riches include the exhibition of all three of Cook’s major voyage journals, in his own handwriting: the National Library’s Endeavour journal and its counterparts for the second and third voyages, both on loan from the British Library. We cannot find any evidence that they have been displayed together before. These journals are the best surviving record of how Cook experienced the three voyages, in his own words. The published versions of the journals were edited—in the case of the Endeavour voyage journal, heavily.

At the exhibition’s heart are four manuscripts. These are open to pages presenting voices from the voyages. In Joseph Banks’ journal is a wordlist of Guugu Yimithirr from Endeavour River in 1770. In surgeon David Samwell’s journal, a transcription of haka and a lament from Tōtaranui, Queen Charlotte Sound, in 1776—it is the earliest substantial record of Māori language. In Cook’s own third voyage journal is a long wordlist from Nootka Sound, recorded in 1778. And finally, in the Library’s copy of Cook’s Secret Instructions, are the voices of the Lords of the Admiralty in 1768, instructing Cook to search for the Great South Land on his Endeavour voyage.

Wordlist from Nootka Sound (Vancouver Island), North Pacific, f. 413r in James Cook, Journal 1776–1779, British Library, London, Egerton MS 2177 A © British Library Board

While most of the exhibition is arranged by place, there is a significant prelude and coda, which envelop this geographical core. Two screens at the beginning of the exhibition put First Nations people at the forefront of the exhibition. Traditional custodians of the Australian Capital Territory provide virtual Welcomes to Country and First Nations people of the Pacific greet visitors in different ways. Images of Cook and Cook-like figures explore how people continue to respond to Cook’s image, reflecting discussion about his role in history and the effects of his expeditions. Cook’s humble beginnings in Yorkshire and the Whitby coal trade, his experience in the Royal Navy in North America during the Seven Years’ War, and European and Pacific navigation traditions are all explored. Highlights include the original plans of the Endeavour from the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and depictions of Pacific First Nations craft.

The first stop in the exhibition is Totaiete Mä, the Society Islands, now part of French Polynesia. Cook’s voyages came to know it well, first going there to observe the Transit of Venus on 3 June 1769. The section considers the people Europeans met there and their customs, such as tattooing and funerary rituals. A highlight in this section is a partial Chief Mourner’s costume. It is one of at least ten collected on Cook’s second Pacific voyage, on loan from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Costumes like these were used in funerary rituals in the Society Islands. It would have been worn by a relative of the deceased, who would rampage around the village, scaring all who crossed his path. Expertly made of precious materials, the costume is extremely fragile.

Chief Mourner’s Costume from the Society Islands, 1700s, Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, FE000336/1-5, Gift of Lord St Oswald, 1912

Cook’s ships spent more time in Aotearoa New Zealand than anywhere else on the three Pacific voyages. Cook came, over successive voyages, to use an inlet he named Ship Cove at Tōtaranui (Queen Charlotte Sound) as a base for venturing further into the Pacific. Interactions between the British and Māori involved trade and genuine cultural respect, though also miscommunication and violence. A large, two-part manuscript map of New Zealand by Cook, on loan from the State Library of New South Wales, represents one of his great achievements, completing the European map of New Zealand.

Cook’s ships visited the east coast of New Holland (Australia) on all three Pacific voyages, but the most exhaustive encounter was the Endeavour’s passage northwards between April and August 1770. The local people managed the land in ways mostly unseen by the Europeans. Interactions at Waalumbaal Birri (Endeavour River), where the voyage remained for 48 days repairing the ship, were the most sustained, and involved a dispute about resources (green turtles) and a gesture of reconciliation by an old Guugu Yimithirr man.

We are fortunate to be able to showcase many of the major records relating to the Endeavour voyage, most from the British Library and The National Archives (UK). The Library’s Endeavour journal in Cook’s own handwriting, is displayed beside the version submitted to the Admiralty at the voyage’s end, now held by The National Archives (UK). Both journals are open to the tense days after the Endeavour struck the Great Barrier Reef in June 1770. The first has dramatic revisions, use of the margins, and even a flap; the second proceeds in the calm, rhythmic hand of Cook’s clerk Richard Orton, who has turned Cook’s draft into a final version. In a very graphic way, this contrast between the entries shows the care, if not the agonising, Cook took over his journal. Cook wanted to get his account just right. Other manuscripts include the ship’s official log and muster book, artist Sydney Parkinson’s voyage sketchbook and officer Richard Pickersgill’s maps of Botany Bay and Endeavour River. A highlight is the watercolour by Tupaia of Aboriginal people fishing at Botany Bay in late April 1770. Tupaia was the Polynesian navigator who joined the voyage in 1769 in Tahiti. Botanical specimens from the National Herbarium of New South Wales in Sydney join a pencil drawing, watercolour and a copperplate of a grevillea pteridifolia from the Natural History Museum, London.

Cook’s voyages visited many places in the Pacific, some briefly, from the far south to the far north. These travels are explored through scenes of places visited and portraits of people met, drawn largely from the Library’s own collections. The exhibition’s journeys end in Hawaii, where Cook was killed at Kealakekua Bay in 1779. The swordfish dagger reputedly used to kill him is displayed near his last log.

John Webber, Manner of Travelling in Kamtschatka, 1779, nla.cat-vn690135

The last parts of the exhibition consider responses to Cook in the years since his death. They examine how Cook’s voyages were written up, memorialised and reflected in art, politics and humour. To some, the voyages led to events that undermined sovereignty and initiated human tragedy. To others, Cook’s legacy has been woven more readily into national histories and identities. The question of how perceptions of Cook have evolved since the 1770s continues to inspire artists and fuel debate.

The Library has reached out to all the First Nations Communities from places featured in the exhibition. Some have kindly agreed to be filmed, and have recorded words from wordlists dating from Cook’s voyages and shared their insights and opinions on them. They can pinpoint miscommunications as well as genuine connections. These wordlists are available on two touchscreens. Nearby, a spinning 1790 Cassini globe traces Cook’s three Pacific voyages in a half-globe multimedia projection. With voices and places of the voyages central to the exhibition’s approach, it is hoped this exhibition will broaden, surprise and challenge perceptions, as well as absorb, in its new look at Cook and his Pacific voyages.

Dr Susannah Helman curated Cook and the Pacific with Dr Martin Woods. The exhibition will be on display between 22 September 2018 and 10 February 2019.

View the story on the National Library of Australia website.