In Search of a Northwest Passage

MASTER MARINER JAMES COOK AND CANADA’S OCEAN GATES

By Barry Gough, Maritime and Naval Historian, Royal Military College of Canada

The mission of Cook’s third voyage to the Pacific Ocean was to find, if it existed, a western outlet of the Northwest Passage. Given the fact that the Hudson Bay Company’s Samuel Hearne had made voyages overland from Hudson Bay that dispelled prospects of a Northwest Passage in those more southerly latitudes, all reasoning seemed to suggest a waterway somewhat higher. Russian charts suggested an opening in 65 degrees North latitude, and that is what Cook decided on, writing his own instructions.

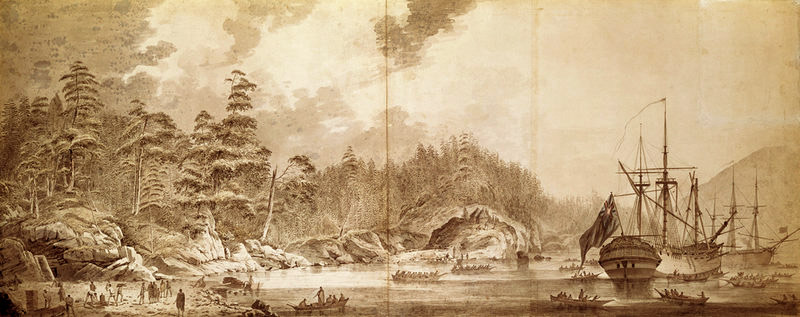

Many had talked about the Northwest Passage over the centuries. Juan de Fuca, sailing for the King of Spain in 1592, claimed just such a discovery. However, Cook disparaged armchair geographers and boastful mariners. Cook let suspicion get in the way of inquiry– and he compounded his error by missing the entrance to this great western portal of the American continent. Cook also had not known that Nootka Sound was part of a large island, Vancouver Island. In large measure, this distant Northwest Coast, lying 18,000 sea miles from England, Halifax or Boston was the world’s best-kept secret. With its immense timber and mineral resources, its excellent harbours and potential materials for industry, and its First Nations (who unlike some tribes elsewhere within the Pacific Rim bore no hostility to the newcomers) were agreeable to trade. The great sea resources of this locale – whales (and whale oil), fish and, above all, sea otter – were the inducement for future voyagers to visit Nootka, who used it as a base of summertime operations (ship repair and construction) and security from the rough seas and offshore winds that can whip this coast.

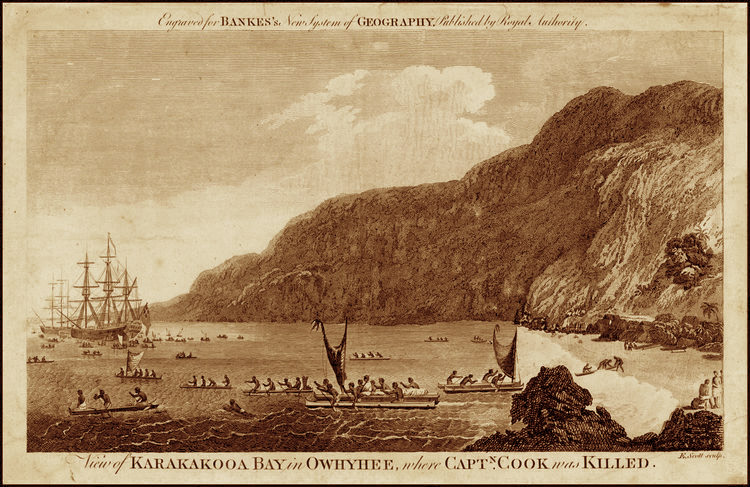

Resolution and Discovery in Ship Cove, Nootka Sound, by John Webber, 1778 (National Maritime Museum)

Cook sailed in the Resolution and Discovery from the Hawaiian Islands and sighted the high and snow-clad coast of New Albion (as Drake had dubbed it) on 7 March 1778. Sailing north, passing the entrance of Juan de Fuca Strait (as said) he was urgently looking for a place to take on wood and water – the former for drinking, the latter for keeping the stoves hot for the cooks and crew. Nootka Sound’s southern entrance presented itself that famous day of 29 March 1778.

Man of Nootka Sound, John Webber, 1778

The inhabitants did not understand what the strange vessels were. Oral tradition among the Mowachat holds that they spied one sailor with a hooked nose and another who was a hunchback. They identified them, in turn, with the dog salmon and the humpback salmon, an indication of their fish-like origins. They thought Cook’s ship to be “a fish come alive into people,” and, consequently grew cautious. A chief told them to go out to the ships again and try to understand what the newcomers wanted and what they were after. They did so and Cook’s crew gave them ship biscuits. The Mowachat decided that the whites must be friendly and that they, in turn, should welcome the strangers. Thus they gestured, all the while telling Captain Cook, “Nootka, Itchme Nootka, Itchme” – meaning “you go round the harbour.”

Interior of Habitation at Nootka Sound, John Webber, April 1778

Mowachat and Muchalat welcomed the ships and urged the mariners to come into harbour, “to go around,” and anchor. Cook’s men were understandably anxious, not knowing the navigation, for the water they tried unsuccessfully to sound with their plumb bobs was extremely deep in these channels. Moreover, the day was drawing on, and the ships needed to be secured for the night for precautionary measures, away from the native village. This last was Yuquot, “where the wind blows,” the summer village that was situated on the southern promontory of Nootka Island, within the entrance. For this reason a cove of safety was selected – “Ship Cove” it is named. A young master’s mate named William Bligh, who later attracted much notoriety on account of the mutiny on the Bounty, conducted a survey of Bligh Island and vicinity. Other surveyors, including Henry Roberts, took up the task and by the end of four weeks a reasonably accurate survey had been completed. An engraving of it was published in Cook’s voyage account, completed and published in authorized edition in 1784. That engraved chart, as well as the grand chart compiled from various sources by Roberts of the Northwest Coast and the North Pacific, are prized collector items these days.

Chart of the NW Coast of America by Henry Roberts, 1784 (click to enlarge)

As to the trade with the First Nations, over the course of days the native numbers increased as word spread that the ships were in harbour. Cook’s voyage account states:

“…we received most benefit from such of the natives as visited us daily. These, after disposing of all their little trifles, turned their attention to fishing and we never failed to partake of what they caught. We also got from these people a considerable quantity of very good animal oil, which they had reserved in bladders. In this traffic some would attempt to cheat us by mixing water with the oil; and, once or twice, they had the address to carry their imposition so far as to fill their bladders with mere water, without a single drop of oil. It was always better to bear with these tricks than to make them the foundation of a quarrel; for our articles of traffic consisted for the most part of mere trifles; and yet we were put to our shifts to find a constant supply even of these. Beads, and such other toys, of which I had still some left, were in little estimation. Nothing would go down with our visitors but metal…” Cook relates that this native society was hungry for metal. Brass had supplanted iron as the native preference. So eagerly sought was brass that hardly a bit of it was left in the ships, except that belonging to the instruments of navigation. “Whole suits were stripped of every [brass] button; bureaus of their furniture [hardware]; and copper kettles, tin canisters, candlesticks, and the like, all went to wreck….”

Soon it was time to sail to attend to the real focus of this mission, finding a Northwest Passage. Before long, Cook’s ships were in the area of Cook Inlet, southeastern Alaska, near where Anchorage is today. Cook explored as far as he could up what he called “Cook’s River,” and at Point Turnagain reversed his course and headed for locales like Prince William Sound, Shumagin Islands, Unalaska, then north again to Bristol Bay, through Bering Strait and even as high in latitude as Icy Cape above 70 degrees North. No Northwest Passage was found.

Resolution Beating Through The Ice, John Webber, 1778 (click to enlarge)

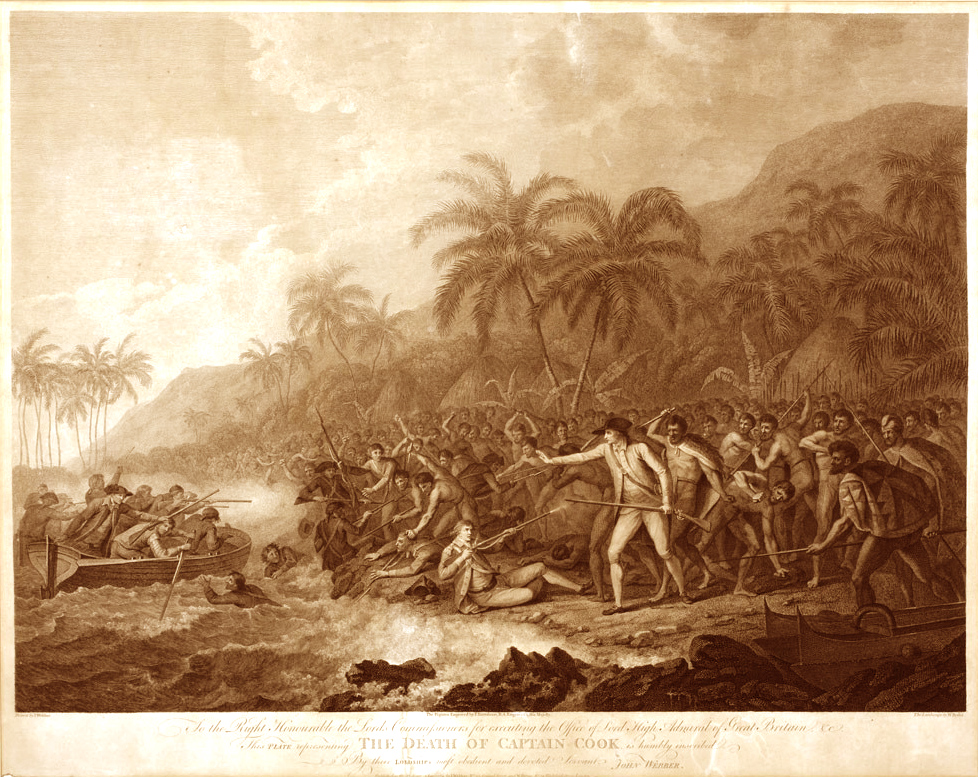

In late 1778 Cook returned to Hawaii for food, rest and repair. In an extraordinary set of circumstances in which Cook was largely blameless, he was killed by Hawaiians at Kealakekua Bay, the Big Island of Hawaii on 14 February 1779. That summer his ships continued their northern exploration. The maritime fur trade which Cook had thought might be carried on along the Northwest Coast did not require a discovery of a Northwest Passage after all. At Canton, the sea otter pelts collected on the Northwest Coast fetched high prices. Soon various private merchant adventurers were fitting out ships for Nootka and the Pacific coast, while after four years at sea, Cook’s weather-beaten vessels arrived back in Britain. Their crews recounted the final testimony of the famed captain (and others who had died). But the most remarkable fact of all was that only seven men had died from sickness and not one from scurvy.

Death of Captain Cook, by John Webber, engraved by Francesco Bartolozzi and William Byrne

James Cook had hinted at the future by pointing to the promise of the Pacific world. He had given the exact latitude and longitude of the entrance to Nootka Sound. Mariners now knew of a safe port on a wild and relatively unknown shore. But in addition, the dimensions of the Continent had now been measured east to west. Seventy degrees of longitude separated Cape Race in Newfoundland from Nootka Sound, 6500 kilometers (4000 miles) to the west. The span of the future Canada could now be imagined, for Cook’s careful surveys in what is now Atlantic Canada and in the Gulf and River St. Lawrence were linked by the time of his death to the prospects of a “distant dominion,” as parliamentarian Edmund Burke called it, on the Northwest Coast. As the statue to the resolute navigator that stands beside Admiralty Arch in London says, Cook “traversed the gates of Canada both east and west.” That’s a memorial enough for any person, and it places him high in the annals of Canada. Cook, it may be said in closing, did more than any other person to make the world one, and in a sense he did as much as anyone to determine the size, dimensions and ocean outline of Canada.

.