Bellin Map (1754), Cook Map (1776), Cook & Google Map, Google Map

Newfoundland Surveys (1763-1767)

JAMES COOK IN NEWFOUNDLAND, 1763-1767

By Dr. Olaf Janzen (Grenfell Campus, Memorial University of Newfoundland)

With the restoration of peace in 1763, James Cook, Master of Northumberland, was paid off. Yet this was the moment when the contacts and connections that he had developed by then as a master in the Royal Navy came forcefully into play. Hugh Palliser, who had encouraged Cook to take his Master’s examination in 1757, served as commander-in-chief of the Newfoundland station ships for most of the time that Cook spent surveying the coasts of Newfoundland Labrador. Alexander, Lord Colvill, praised Cook’s skills as a chart-maker in a letter to the Admiralty Secretary, remarking on his “Genius and Capacity” and declaring that Cook’s work “may be the means of directing many in the right way, but cannot mislead any.” But of the several individuals who had helped shape Cook’s career, one of the most important surely was Thomas Graves.

Graves was both commander-in-chief of the Newfoundland station and the civil governor of the Newfoundland fisheries when the French captured St. John’s in 1762. He had been impressed by Cook’s cartographic work while serving as Northumberland’s master during the expedition to dislodge the French. Now, in 1763, and still serving as commanding officer of the Newfoundland station and civil governor, he was acutely aware of the way that the Peace of Paris had greatly expanded his jurisdiction – the administration of coastal Labrador had been added to his many other responsibilities, and he knew next to nothing about that region. Graves therefore urged the Admiralty to commission a survey of the coasts of Newfoundland, and he recommended Cook as the person best suited for the job. Thus it was that, in the spring of 1763, Cook found himself returning to Newfoundland, this time with an appointment as Surveyor of Newfoundland.

His first assignment was to prepare a chart of the island of St. Pierre. This had to be done quickly, for St. Pierre and Miquelon had been restored to the French by the terms of the Peace of Paris, and they were anxious to take immediate possession. Indeed, on the very day that the Tweed, Capt. Charles Douglas, arrived in St. Pierre with Cook on board, so did two French warships and the new French governor. Douglas stalled for time while Cook hastily completed a superb chart of St. Pierre; it was a masterful indication of Cook’s ability to work under pressure. Once that work was done, he immediately headed north to the Northern Peninsula, charting harbours there where treaty privileges allowed the French to fish. He also survey several of the harbours on the Labrador shore which was now under British jurisdiction.

By starting first with St. Pierre and then heading to the Northern Peninsula, Cook was revealing something about British Admiralty priorities. Every coast that he was directed to chart was sensitive in some way to British efforts to assert their sovereignty over territory which had been French (Labrador), which was about to become French (St. Pierre and Miquelon), or where the French had been encroaching (Newfoundland’s South Coast). Thus, Cook returned to the Northern Peninsula in 1764 to complete his survey of the coast most frequented by French fishermen.

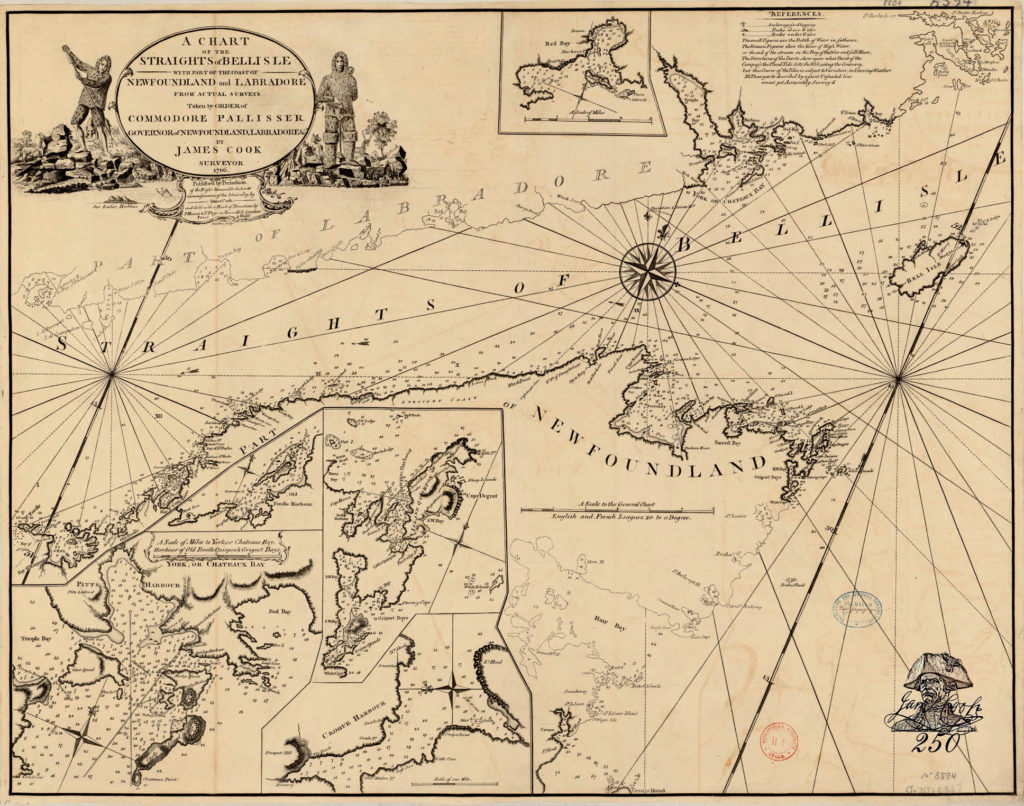

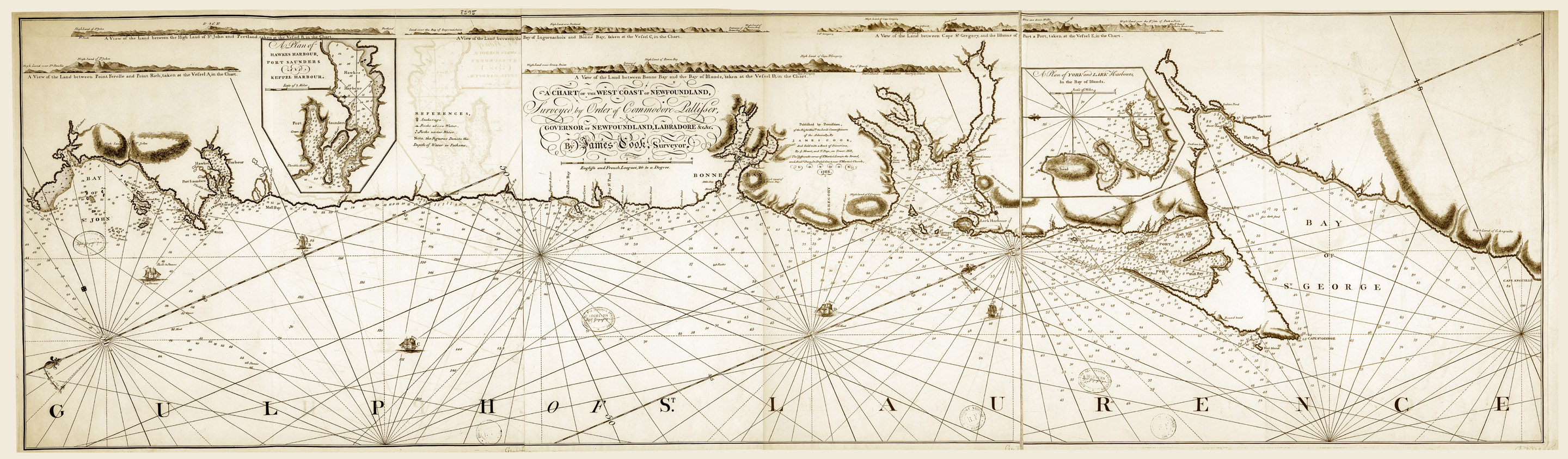

A Chart of the Straights of Belle Isle – By James Cook, Published 1766

In 1765, he turned his attention to the South Coast, from the Burin Peninsula to Bay d’Espoir, where the French at St. Pierre had been engaging in illicit trade with local residents and even over-wintering and engaging in furring, wood-cutting and vessel construction, all in violation of existing treaty restrictions. Cook completed his survey of the South Coast in 1766, from the Bay d’Espoir area west to Cape Ray and Codroy. And in 1767 he surveyed the West Coast, a region virtually unknown to the British and where the British needed to forestall French efforts to claim that coast as part of the so-called “Treaty Shore.”

The quality of Cook’s survey work was unprecedented, and understandably so. Despite the fact that both Great Britain and France regarded their fisheries at Newfoundland as both economic and strategic assets, neither country had a good understanding of its coastlines; there were surprisingly few charts of the island and almost none of particular bays or stretches of the coast. The French had established a Depôt des Cartes et Plans de la Marine in 1720, and had subsequently undertaken a cartographic survey of the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the 1730s, yet their charts were woefully inadequate – one early eighteenth-century traveller compared navigation in that region to “walking blind-folded and barefoot in a room of jagged glass.” As for the British, they had even fewer charts, and most of these were laughably crude. Yet accurate charts were increasingly recognized as essential in defining boundaries and answering questions of sovereignty and jurisdiction. The survey work that Cook performed so diligently in Newfoundland between 1763 and 1767 was therefore perfectly consistent with British determination to assert sovereignty more forcefully over those parts of Newfoundland and Labrador which, until then, government had virtually ignored.

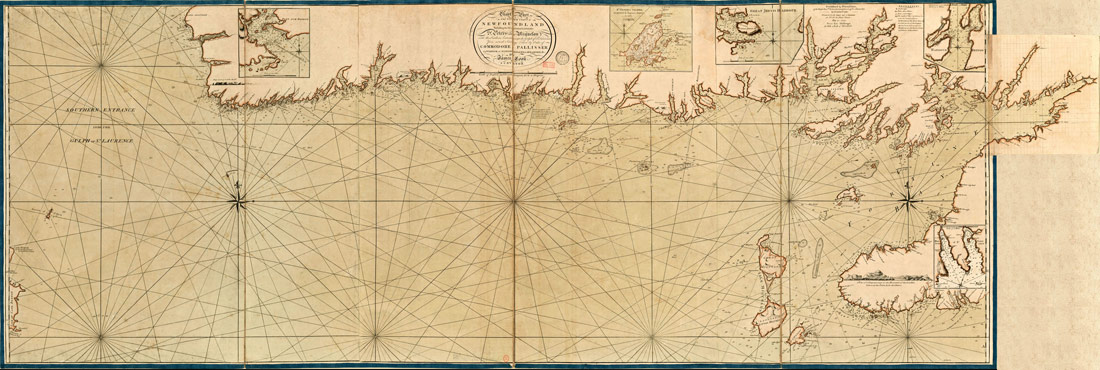

A Chart of Part of the South Coast of Newfoundland – By James Cook, Published 1774 (click to enlarge)

To conduct his surveys, Cook developed a regular routine which combined Samuel Holland’s technique of land-based trigonometric surveys with work by small boats on the seaward side. First he would accurately measure his baseline and the angles to a distant object (often points on land marked by flags that his crew carried ashore). He then noted this information on paper using a plane table before plotting a set of triangles anchored to the fixed positions. Meanwhile, men using small boats measured water depths with sounding leads while taking cross-bearings of the same fixed positions that had been taken on land. Finally, these data were integrated into a composite land-sea survey.

At the end of the season, Cook took the drafts made during the summer back to England where he prepared the final copies. These master copies were massive – sometimes five or six metres in length. These were obviously too unwieldy for shipboard use, yet they were charts of exquisite accuracy and detail. Cook took painstaking care to annotate the charts with detailed observations on the navigational challenges as well as the potential for the fishery of the many harbours, coves, and bays that he surveyed. These annotations were consistent with the Admiralty’s expectation that all masters and captains were to record detailed information about unfamiliar coasts which were recorded in what became known as remark books. And since the information and accuracy of his charts gave them commercial value, Cook received permission to have smaller black-and-white copies published for general sale.

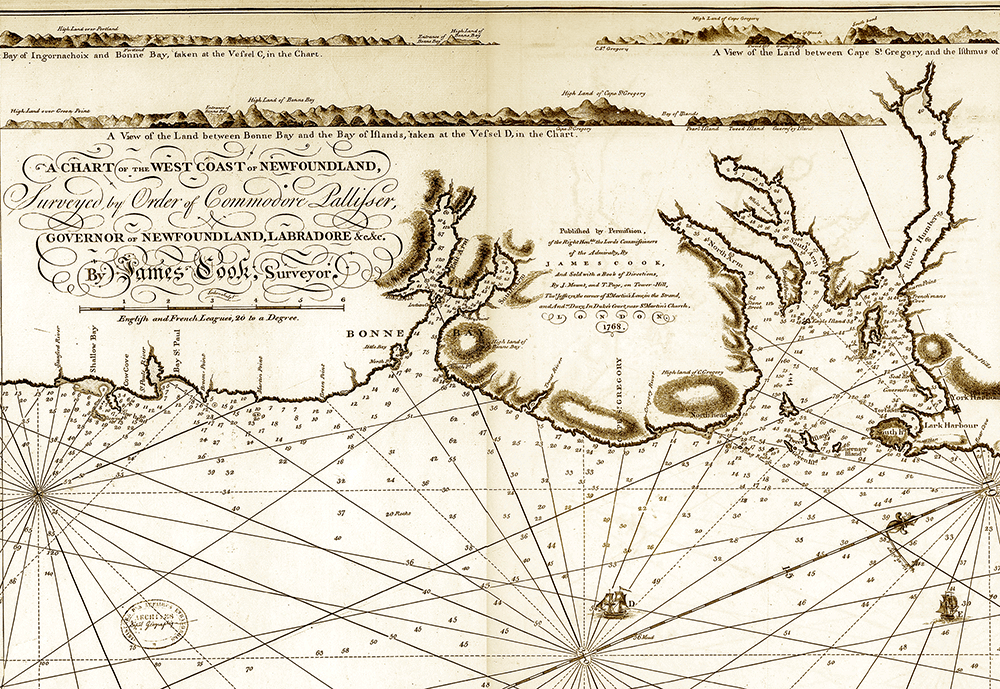

A Chart of the West Coast of Newfoundland – By James Cook, Published 1768 (click to enlarge)

A Chart of the West Coast of Newfoundland – By James Cook, Published 1768 (click to enlarge)

The decision to take Cook away from Newfoundland following the completion of the 1767 survey season, and to reassign him to the first of the three Pacific voyages, is usually attributed to the quality of his cartographic skills. Certainly the quality and thoroughness of Cook’s cartography must have been key factors in the decision. Yet Stephen Hornsby also emphasizes that “Cook was the only viable candidate in the navy who could both survey a coastline and command a ship.” Cook had been assigned a New England schooner in 1763 which Thomas Graves had purchased so that Cook would not be dependent on vessels on loan from the navy. This was the Grenville, and the schooner – soon re-rigged by Cook as a brig on the grounds that a brig’s square rigging was better suited for the close inshore work demanded by his survey work – served him well through his years in Newfoundland.

Those years were not without incident. Members of Grenville’s crew got drunk while making spruce beer in 1764 and had to be disciplined. Cook himself suffered serious injury (scarring him for life) that same year, when a powder horn ignited in his right hand in the aptly named Unfortunate Cove. The Grenville ran aground in 1765 in Bay D’Espoir and had to be repaired with the resources at hand. And at all times, from 1763 to 1767, Cook was more or less entirely on his own. Apart from the occasional fishing vessel or merchant trader, and, even less frequently, a warship assigned to the Newfoundland station, Grenville rarely came into contact with other ships. Almost every coast was uncharted, and as Robson recognizes, “Extra responsibility was quickly thrust upon Cook’s shoulders…. Working this way in isolation was ideal preparation for taking a ship to the Pacific.” Few of Cook’s biographers give Cook’s command experience its due when explaining the decision to appoint him to the Pacific.

Detail from A Chart of the West Coast of Newfoundland – By James Cook

Published 1768 (click to enlarge)

Thus, Cook’s service in Newfoundland was critical to his appointment to the Pacific voyages. That service began in 1762 with his role as Master of Northumberland during the British response to the French raid on the Newfoundland fishery. This was then followed between 1763 and 1767 by his service as the consummate surveyor and cartographer that he proved himself to be. His Newfoundland experience also provided him with essential command experience – an experience that proved critical to the next great transition in his life. By 1768, Cook’s performance and the quality of his work on the Newfoundland survey had so impressed the Admiralty that they would terminate his service in Newfoundland before it could be completed, sending him instead – as a newly commissioned lieutenant of the Royal Navy – on the first of three great voyages of exploration into the Pacific.

In introducing his book, Captain Cook’s War and Peace: The Royal Navy Years, 1755-1768, John Robson remarked that “Some writers have asked the question, ‘Why was James Cook chosen to lead the [first Pacific] expedition?’” Robson then suggested that, with a better understanding of Cook’s career between 1755 and 1767, the more reasonable questions to ask would be “‘Why would the Admiralty have chosen anyone else to lead the expedition?’ and ‘Who else could they have chosen?’.” It was a point with which the foremost Cook biographer of them all, J.C. Beaglehole, agreed, saying that “Cook was to carry out many accomplished pieces of surveying, in one part of the world or another, but nothing he ever did later exceeded in accomplishment his surveys of Newfoundland from 1763 to 1767.” If the Pacific made the explorer, then Newfoundland made the cartographer.

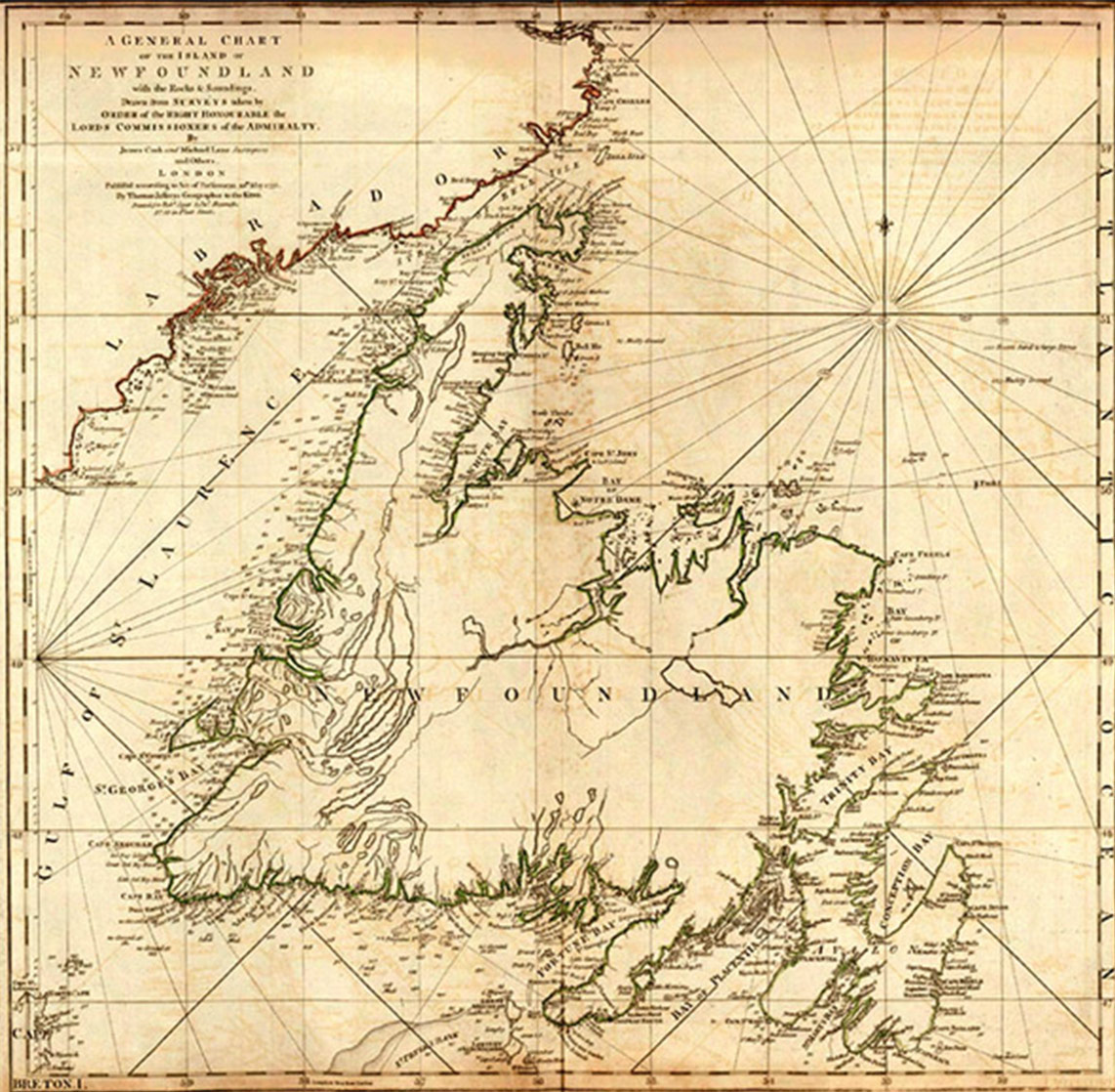

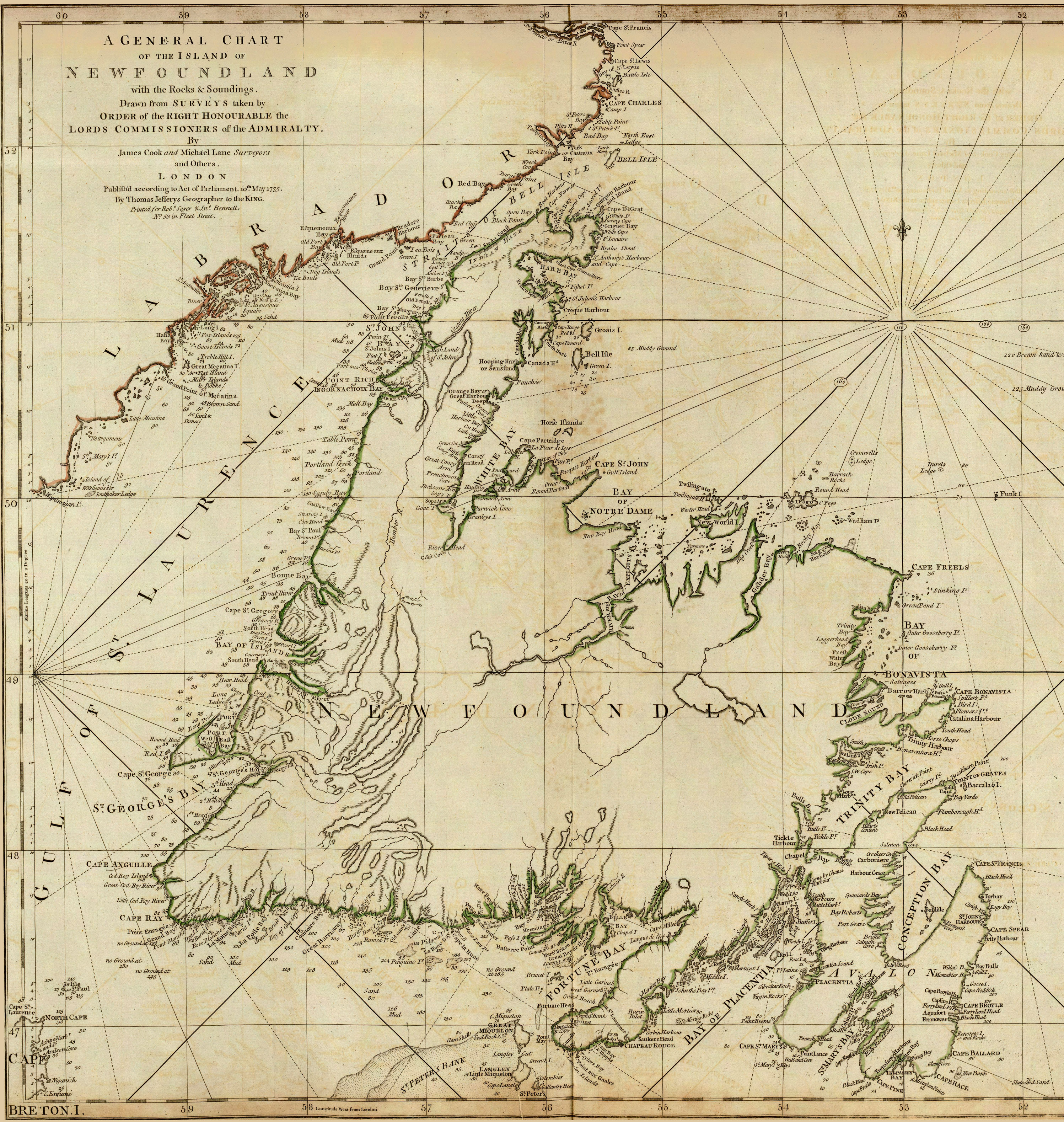

A General Chart of the Island of Newfoundland

A General Chart of the Island of Newfoundland

By James Cook and Michael Lane, Published 1775