This year marks the 250th anniversary of James Cook’s arrival in Australia. Explore the legacy of Cooktown, the final stop of his tour.

24 June 2020

On a clear, breezy June night in 1770, the Great Barrier Reef’s coral talons tore into the hull of the HMS Endeavour. Briny water flowed into the wound and men ran around shouting in a language never before heard in this particular part of the world. The commander coolly ordered the ship ashore to repair the damage.

Strong gales and heavy showers obfuscated the crew’s efforts to land, but eventually the ship hobbled into a harbour and moored on a beach. Her commander, Lieutenant James Cook, stepped ashore to survey the scene and plot a way out. The layover, intended to take mere days, would become one of the most momentous in the history of modern Australia.

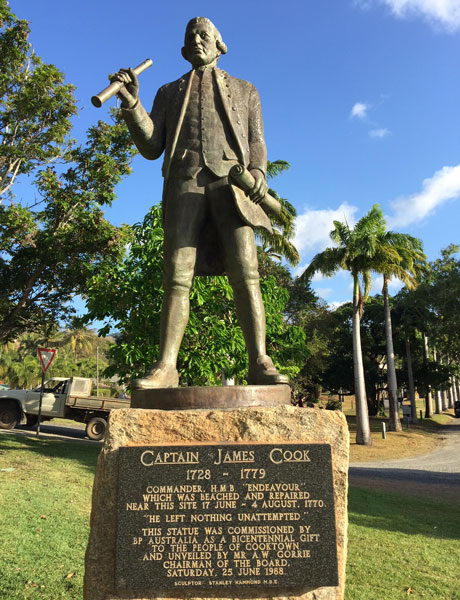

One of many monuments to Captain James Cook that preside over the town

Two hundred and fifty years later, the weather is much kinder to me as I belt up the long, dry inland highway from Port Douglas north to Cooktown. My journey began in Sydney, and largely followed the path of the Endeavour as she made her way up Australia’s east coast in 1770.

Cook bounced along the shore like a skipping stone across a tranquil river, only colliding with the New World a handful of times. His stops at what we now know as Kurnell, at the southern end of Sydney, and both the Town of 1770 and Cooktown in Queensland were the dawn of modern Australia.

Growing up in Sydney, I was well acquainted with Botany Bay, but Cooktown had always intrigued me. I later learned of Cook’s extended journey north, his reticence about the country he’d encountered, and his reluctance to return on either of his subsequent journeys around the world. What had happened up in Cooktown, his final stop on the mainland, to sour him?

Even without the history, modern Cooktown’s remoteness enhances its mystique. It’s as far north as many dare to drive; roads beyond Cooktown aren’t as reliably sealed, and a 4WD is recommended. Those with sea legs, however, can moor in the harbour for the true Cook experience.

With a population of 2600 or so, Cooktown is much bigger than I’d imagined. It stretches from the summit of Mt Cook to the Endeavour River far below. The main street is a vibrant strip of restaurants, pubs, shops and cultural centres. From the top of the imaginatively named Grassy Hill (another of Cook’s nomenclatures), it’s possible to look out across the entire town and off towards the Great Barrier Reef. It was from here that Cook surveyed the scene of his makeshift dry dock two and a half centuries ago.

In his time, Cook’s view was of Gan-Garr, a small clearing in the Guugu Yimithirr estate of Waymburr. At the Cooktown History Centre, Alberta Hornsby tells me it was about the safest place they could have landed. “They arrived in a place that was, for the Guugu Yimithirr people, a place of peace and non-violence,” she says. “A bit further north or south and they might not have made it home.”

Forced by fate to coexist for 48 days, Cook and his botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander came to have a greater understanding of the Guugu Yimithirr than they’d been able to with the Indigenous people further south.

Today, Cooktown is a bustling, self-sustaining country town. Tourism is its bread and butter: those looking for a wilder Tropical North Queensland experience than is possible at the increasingly trendy Port Douglas and Mission Beach will be well-served here. There are long stretches of empty beaches, bushwalks in the nearby national parks, a thriving birdwatching scene, and world-class fishing – all totally independent of the Cook legacy.

Nick Davidson, captain of my sunset river boat cruise with Riverbend Tours, offers his own take on the town. “The belief for a long time was this town was slowly dying, but at this point it’s not going anywhere,” he says. “With the anniversary commemorations, scheduled for 2021, I’m confident we will be front of mind again.”

Back in 1970, when the town celebrated 200 years since Cook’s landing, even the Queen made an appearance to mark the bicentennial. But in the years since, Cook has become a polarising figure in Australia: to some he’s a tool of empire and condemned the First Australians to a dark fate; to others he’s a hero and legend of naval lore. “We don’t romanticise what happened here,” Nick says. “It’s just something to learn from.”

For Europeans, Cooktown has always been a place of learning. For example, it was the site of their first encounter with the animal known as a ‘gangurru’ to the Guugu Yimithirr. “Every mob has its own name for it [the kangaroo], but ours was the first the Europeans heard,” Alberta says. “It’s nice to know that today, there’s a little piece of our language known around the world.”

Today, the learning continues. The James Cook Museum provides a comprehensive and refreshing take on the Cook saga: a clear account from an Indigenous point of view. “There’s a big difference between the events of 1770 and 1788, and we need to understand what that is,” says the museum’s heritage officer, Harold Ludwick. “Cook was respectful, and he was working class. It was Banks, a rich man who never had to work to achieve his position in society, who suggested the British return to colonise New Holland, not Cook.”

The James Cook Museum

The museum also covers Cooktown’s subsequent history as a gold mining town, missionary zone, and strategic base against the Japanese advance during the Second World War.

There’s a deep love for the town here, right down to the cute ‘Captain Quack’ rubber ducks in British naval attire sold in the gift shop.

Back at the History Centre, Alberta describes the Indigenous relationship with Cook as complex: “Many elders in my mob won’t talk about Cook, but I think we need to better understand what went on here.” What went on was the first reconciliation between First Australians and Europeans, after an altercation over the death of a pig. For the past 60 years, an annual reenactment of that peacemaking has been staged at Reconciliation Rocks.

While the man himself never returned to Australia, we’ve never let him go. When I ask if she feels being tied so closely to Cook has obscured Cooktown’s identity, Alberta shakes her head. “If we stop talking about Cook, we’ll never move past the narrative that Indigenous people are surrounded by negatives,” she says. “We aren’t.” In fact, 2020 might be the start of a second wind for the Cook conversation. “It’ll be the first anniversary where we can speak about our side of the story,” Alberta says. “It wasn’t that way in 1970.” If we’re ready to reevaluate the events of 1770, perhaps we can learn from Cooktown’s legacy as a site of peace and mutual respect.