“The Death of General Wolfe” by Benjamin West, 1770

French and Indian War (1758-1762)

JAMES COOK AND THE FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR

By Victor Suthren (Writer / Captain Cook Society)

and Dr. Stephen Hornsby (Canadian-American Center / University of Maine)

James Cook had entered the Navy in 1755, for reasons of his own and much to the astonishment of both the Walker brothers whose employ he left, and the Royal Navy, who were only too pleased to receive him into pay. At the time of his entry into the Navy he was a highly competent coastal mariner who had learned his trade in the Walkers’ colliers along the treacherous North Sea coast and on a few passages to Ireland and Norway. His practical seamanship was unmatched, and combined with his physical and personal qualities to produce promotion out of the ranks of the common seamen within a month of his joining the Navy. His scholarly self-instruction in mathematics and the scientific bases of navigation were not yet developed to a similar degree, however, and it would only achieve a equal level of competence with his physical seamanship when he had had the benefit of additional encouragement from perceptive commanders such as Hugh Palliser of Eagle, and, in particular, John Simcoe of Pembroke, under whom Cook first came to North American waters.

The outbreak of the Seven Years War between Great Britain and France in 1754 led to a worldwide conflict that ended in British triumph in 1763 and massive expansion of its global empire. A significant part of the war (often known as the French and Indian War) was fought in North America. James Cook played a small but important role in this conflict, which prepared him for his later success in the Pacific.

After disastrous landward campaigns against the French in North America in the early years of the war, the British switched to a maritime strategy that soon produced success. The French position in North America rested on Québec, the great fortress town commanding the St. Lawrence River. The French fortress of Louisbourg on Île Royale (Cape Breton Island) served as Québec’s outer bulwark at the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. British maritime strategy depended on capturing Louisbourg and then moving up the St. Lawrence to attack Québec.

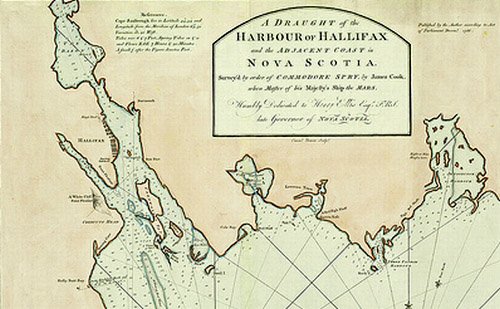

The British assault was prepared at Halifax, capital of Nova Scotia and Britain’s major military base in North America. Cook arrived in the port city in spring 1758 as master of HMS Pembroke, part of the great naval force assembled to attack Louisbourg. The Pembroke joined the blockading British fleet in June, helping support the army on land as well as bottling up French warships in Louisbourg harbour. After the French capitulated in July, the British surveyed the captured town. Army surveyor Samuel Holland, who had worked closely with brigadier general Wolfe in the bombardment of the fortress, surveyed and mapped the town and surrounding countryside. In an encounter that would later have enormous significance, Cook met Holland while he was surveying the British landing place at Kennington Cove. As a ship master, Cook knew the principles of navigation but knew little, if anything, of land surveying. Ever keen to improve his education and knowledge, Cook joined Holland the following day in the survey of White Point and began to learn the rudiments of plane table surveying and topographic mapping.

Samuel Holland

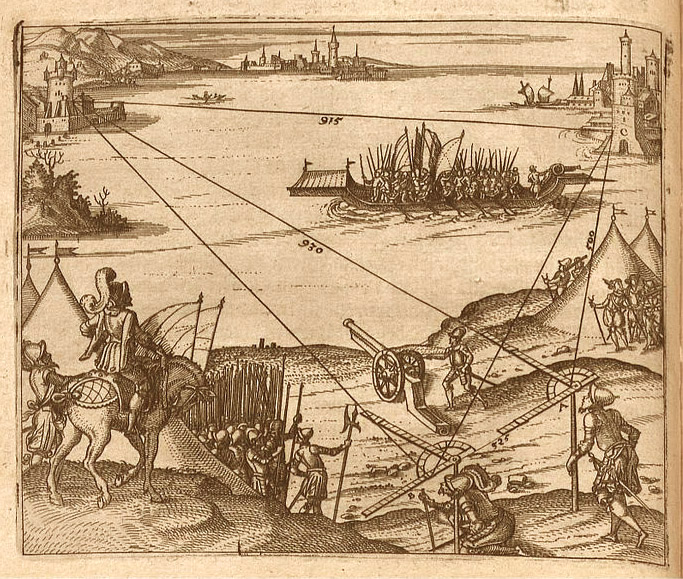

Plane tables had a small, square flat surface supported on a tripod; Holland would sight over the top of the table at distinguishing marks using a rotating telescope fixed to the table’s centre, and make notes of those observations. Cook learned that the process allowed the creation of an accurate diagram in which all physical features could be placed in correct relation to one another, and to a base line with a known magnetic heading, obtained from a box compass affixed to the table.

Illustration from Leonhard Zubler’s Novum Instrumentum Geometricum (1607)

As Pembroke rode at anchor within the harbour of Louisbourg in the waning summer of 1758, Cook continued to develop his surveying skills under Holland’s tutelage until the demands of war called him to put them unexpectedly to use. Pembroke was dispatched with a small squadron to carry troops into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, where the army was to carry out the inglorious work of burning and destroying French settlements that might send supplies to the colonial capital at Quebec. One of these was the town and harbour of Gaspe, on the mainland. Cook’s reaction to the business of carrying war to a defenceless civilian population is unknown, but he busied himself on the Gaspe expedition with observing, sketching and sounding, doing the latter from Pembroke’s boats and possibly exercising his new land survey skills as well. On the return of the squadron to Louisbourg, Cook appears to have secured from Simcoe permission to spend time penning a chart and survey of the harbour of Gaspe. The result was a carefully-drawn two-sheet effort in a scale of two inches to the mile, and Cook was successful in obtaining its publication in London by Mount & Page in 1759. The publication of this chart of a small, beleagured Canadian port marked Cook’s emergence into the serious realm of surveying and charting beyond the ordinary duty of a Sailing Master.

After the capture of Louisbourg in 1758, the British began to prepare for the assault on Québec. Much of the detailed preparation took place in Halifax, where both Cook and Holland were stationed over the winter. In a famous letter written in 1792 to Lt. Governor Simcoe, son of Captain Simcoe of the Pembroke, Holland described how he “was on board the Pembroke where the great cabin, dedicated to scientific purposes and mostly taken up with a drawing table, furnished no room for idlers. Under Capt. Simcoe’s eye, Mr. Cook and myself compiled materials for a chart of the Gulf and River St. Lawrence.” These charts would be used by the fleet as it sailed up to Québec in summer 1759. Holland further noted that he met Cook in London after his second voyage to the Pacific in 1776. Cook “confessed most candidly that the several improvements and instructions he had received on board the Pembroke had been the sole foundation of the services he had been able to perform.”

John Graves Simcoe, first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, 1792

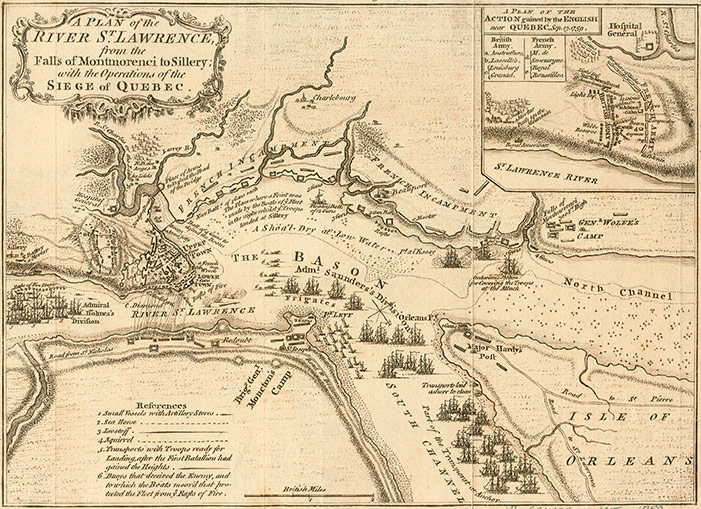

The campaign of Quebec would, according to a grand strategy ordered by Prime Minister William Pitt, be an ascent of the Saint Lawrence with an army like that which had taken Louisbourg, but with orders to capture the city itself. The coming of Spring led to the arrival of troop transports from Britain and a sizeable escort of warships, all under the command of Vice Admiral Charles Saunders, who had replaced Boscawen. Cook’s Pembroke was assigned to an advance squadron under Rear Admiral Durrell that sailed from Halifax on May 5, 1759 and attempted to work its way into the Gulf and River Saint Lawrence, which was choked by an unusually heavy ice pack. With the main force halting at Louisbourg to pick up additional troops for the attack on Quebec, Durrell’s force busied itself penetrating the river and allowing for the discovery of the safe channel—the French had taken up what marks there were—and the completion of a workable chart of the river. In Pembroke, Cook soon found that the compilation of French charts was insufficiently accurate to be relied upon, and took the initiative in forming a sounding flotilla of ship’s boats from the squadron, each carrying that ship’s Master or Master’s Mate, which sounded ahead of the fleet as it advanced up the several hundred miles of the river in stages, depending upon whether the winds were fair or foul. The greatest challenge to this technique came just below Quebec, at the eastern end of the Isle d’Orleans, where the safe navigation channel was known to cross from the northern side of the river to the southern for entry into the wide Basin below Quebec, in a swooping track known as the Traverse. Cook’s boats sounded diligently while the squadron waited at anchor downstream, and discovered that the Traverse was a narrow channel no wider in some places than the extreme beam of some of Saunders’ largest ships. Cook devised a method of marking the channel whereby the flotilla of boats moored themselves as buoys on either side of the channel, marking a clear if constricted passage into the wider anchorage of the Basin. With a favourable east wind, all 140-odd vessels of the fleet sailed one by one in slow majesty through this remarkable assemblage. By June 27, 1759, all of Saunders’ fleet, including his flagship Neptune, 90 guns, had come to anchor in the Basin below Quebec, and the assault could begin.

The siege, however, would last all summer, as the army’s commander, Major General James Wolfe, could not decide on a method of attacking the very formidable French defences, and the towering rocky citadel of the heights of Quebec themselves. Cook was kept busy in sounding those waters that were safe to operate boats in—Indian warriors and Canadian militia would frequently race out in swift birchbark canoes to attack naval longboats engaged in sounding—and had some controversy attached to his name when an abortive assault landing on the Beauport shore below Quebec went awry, at least in part because the assault transports and boats had gone aground on a ledge Cook’s surveys had not reported. Cook’s energy in continuing with the sounding and chartwork, when his other duties would allow, nonetheless had brought him by this point, scarcely a year after first asking Samuel Holland what his strange instrument was called, to be referred to as the ‘Surveyor of the Fleet’. Cook played no direct role, as far as is known, in the September 12th night assault by troops under Wolfe that scaled the heights to the Plains of Abraham by means of the pathway at the Anse au Foulon.

Siege of Quebec, based on a sketch made by Hervey Smyth, General Wolfe’s aide-de-camp, 1797

At the successful conclusion of the siege, when Saunders’ main force was preparing to return to Britain bearing with it the body of James Wolfe, Cook was transferred into Northumberland, 64, which would remain at Halifax over the coming winter and return to Quebec in 1760 to support the garrison the British were leaving behind. Cook used the descent of the river to complete observations made on the way up by both himself and Holland, and on arrival at Halifax was able to complete ‘A New Chart Of The River St. Lawrence’, which was a huge work of some twelve sheets, in dimensions each thirty-five inches by ninety inches, with a main scale of one inch to two leagues [six miles] and an inset scale of one inch to one league. In April of 1760, Vice Admiral Saunders recommended to the Admiralty that Cook’s application to publish this enormous chart folio be granted. Cook’s charts brought a new level of reliable navigation to the great river just as its new custodians needed such reference; but it had been Cook’s leadership in the trying work of finding the passage up for the huge fleet that had provided James Wolfe and his troops the opportunity Pitt wished them to have: the capture and retention of the heart of Canada.

Northumberland lay at Halifax over the winter of 1759-1760, cocooned against the ice and snow, and Cook continued his personal studies of mathematics, navigation and astronomy, ‘bringing in his hand’ as he completed the great work of the Saint Lawrence chart. Cook would return again to Quebec the following summer, albeit briefly, but now entered into a period where his life and activities were centered on Halifax and the routine of the squadron. He nonetheless produced no less than four superb charts of Halifax harbour, and worked with the accomplished military surveyor J. F. W. DesBarres, who like Cook had made land surveying and marine charting into a composite science, and would produce the masterful charting of the Nova Scotian and adjacent coasts entitled The Atlantic Neptune.

Although Cook benefited from his association with DesBarres and other highly accomplished surveyors during his stay in Eastern Canada, it was his contact and period of learning with Holland that was instrumental in launching Cook toward his own apogee of achievement as an innovative maritime surveyor and cartographer. Through instructions that all Masters and Master’s Mates had to observe in 1758, Cook was required as a matter of duty to produce charts and sailing directions for any harbour his ship visited. The quality of these drawings and writings varied as greatly as the capacities of the men who undertook them. For Cook, the electrifying realization which emerged out of the instructional sessions with Holland was that a combination of land surveying methods and accuracy with these established methods of marine sounding, surveying and chartmaking would offer the prospect of new exactitude in the heretofore very inexact science of marine charting. Cook’s signal contribution to the state and competency of marine hydrography was in this innovative exercise of two traditions of observation as a single art with a uniform standard of precision, which raised chartmaking and the recorded basis of navigation to a whole new level. The importance to Cook’s career, and to the history of western exploratory hydrography and chartmaking, of that chance meeting on the windy beach of Kennington Cove near the Fortress of Louisbourg, Cape Breton Island, cannot be overstated.

In 1762, a last French attempt to secure bargaining power in the peace treaty which was to end the Seven Years’ War led to their attack of St. John’s and other ports on the rocky eastern shore of Newfoundland. Northumberland took part in the combined force that successfully forced the French out of Newfoundland waters, and during this service Cook produced charts of Placentia, on the west side of the Avalon Peninsula, of St. John’s harbour, and of two fishing ports, Harbour Grace and Carbonear. In addition, he now produced a compendium ‘Description of the Sea Coast of Novascotia [sic], Cape Breton Island, and Newfoundland’, along with detailed Sailing Directions which would be published in several editions of the Newfoundland Pilot, produced by Thomas Jeffreys in London. So extraordinary was the quality of this work that, at the end of the war when Northumberland was paid off and Cook might have expected to re-enter the struggle for survival in the civilian world, he was retained as a result of requests made by Thomas Graves, governor of Newfoundland, to do further survey and charting work of that island.